Yates Yen-Yu Chao reviews the different types of acne scars and the treatment options available, including lasers and light based systems, punch grafting, and filler injections

Acne is a very common follicular inflammatory disease affecting 80% of adolescent and young adults1. According to a Medline epidemic study, 20% of young people have moderate to severe acne. While 64% and 43% of these patients have their acne persist into their 20s and 30s2. According to a number of surveys, acne is still prevalent in adulthood and predominant in women, with the majority of these patients experiencing stressful facial scarring3,4. The pathogenesis of acne includes a triad of sebum overproduction, hyperkeratotic obstruction of sebaceous follicles, and microbial colonization that promote perifollicular inflammation5.

Prevention is better than cure

Elevated post-acne scars

Tissue destruction results in scar formation. Acne scars can be classified into elevated hypertrophic and depressive atrophic scars. For elevated acne scars, they often occur in patients with a tendency for keloid formation or in areas with higher tension or protruding contours, like the chest, back, shoulder, jawline, nose or mandibular angle7. Elevated scars are notoriously difficult to treat. The treatment options include laser ablation, electrodessication, or surgical excision if they are hypertrophic scars. Keloid scars, different from hypertrophic, are scars with tendencies to invade the peripheral tissue, expanding in size, and growing persistently. Keloid scars should not be treated by way of surface destruction. Other options for the treatment of elevated scars include intralesional injection of steroid8, 5-FU9, bleomycin10,11, methotrexate12, pentoxifylline13, cryotherapy14, silicon sheeting15, topical application of imiquimod16, flurandrenolide, tacrolimus17, and silicon gel18. Intralesional injection of botulinum toxin has been shown to reduce scar formation19. Radiotherapy20 and laser therapy21 have also been reported to be effective for elevated scars. Pressure22, flavonoids23, TGF-3, mannose-6-phosphate24, and IFN25 were also listed as helpful.

Depressive atrophic post-acne scars

The majority of acne scars are atrophic. Atrophic acne scars with different depths, shapes, and sizes should be treated differently. The profile of an atrophic acne scar including the color, margin, elasticity, consistency, distensibility, extent of fibrosis and calcification, and associated primary or secondary comedones or cysts, are all important factors to consider before making a decision on the right treatment plan for the patient.

Volume and surface

Acne inflammation results in tissue destruction. The reason why an atrophic acne scar is depressive is due to the loss of normal tissue. This means loss of volume. According to the extent of inflammation, the loss of volume could occur in the subcutaneous layer (fat atrophy), dermal layer (dermal atrophy), or epidermis (scarring epithelium). Ideally, a complete approach to acne scars should cover both volume replenishment and surface recontouring, and if possible, texture improvement (tissue destruction or regeneration).

Layered reconstruction

The histologic picture of an atrophic scar consists of a thin scarred epidermis, ectatic lymph and venous vessels, collagen, fibroblasts, lymphohistiocytes, remnants of arrector muscles, nerves, debris, giant cells, calcification and lack of an adnexal structure26. Atrophic acne scarring is an issue of damaged skin structures rather than just surface depression or irregularity. Reconstruction of an atrophic scar can be compared to rebuilding a dilapidated house. Building is usually a programmed process of construction from bottom to top. Acne scar reconstruction should also be a layered work from the depths to the surface. And just as a building is composed of a stable foundation, a strong structure, and a beautiful integral façade. For an acne scar, the foundation is the deep tissue that provides enough volume and support. The constituent tissue quality, elasticity, and strength is the structure. While the Façade is the skin surface color and contour.

Ablative and non-ablative lasers

It is a common belief among patients and aesthetic doctors that more light-based treatments could result in more tissue regeneration, which will fill atrophic depressions. However, most of the procedures are performed non-selectively for an area of skin, not for a specific scar. Actually they should be termed resurfacing instead of dermabrasion. Tissue regeneration after non-selective tissue destruction will also be non-selective across the skin’s surface, not only on volume deficient scars. Scarring tissue theoretically has no regenerative capacity, and will not grow unless it is hypertrophic or a keloid.

Ablative lasers work dually by heating the tissue, with subsequent tissue regeneration, and surface sculpting. The surface work of the ablative laser should be focused on modifying the margins of a scar to make them less obvious. Heat destruction results in tissue contraction and regeneration, skin is then tightened and texture improved. Now there are more choices for energy-based devices for skin tightening that also heat the tissue. When talking about the longevities of these energy devices, the author often infers 1.5 to 2 years. But for light-based treatments of acne scars, patients are often encouraged to receive a greater number of treatments to get more satisfactory results but are seldom told that the clinical results are good for only 2 years.

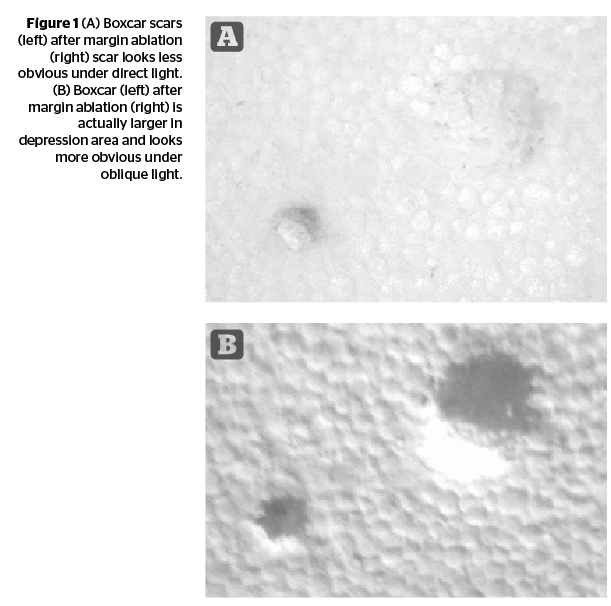

The ablation of the margins of atrophic scars is permanent. The bluntness may make these atrophic scars less obvious under direct light but it actually increases the size of the scars and makes them look bigger when shadows form (Figure 1).

Energy-based devices

In ageing skin, progressive tissue laxity worsens the problem of unevenness around scar tissue29. Aged skin loses its elasticity and descends under gravity, the scarred tissue and the normal ageing skin behave differently. This difference makes the skin appear more uneven.

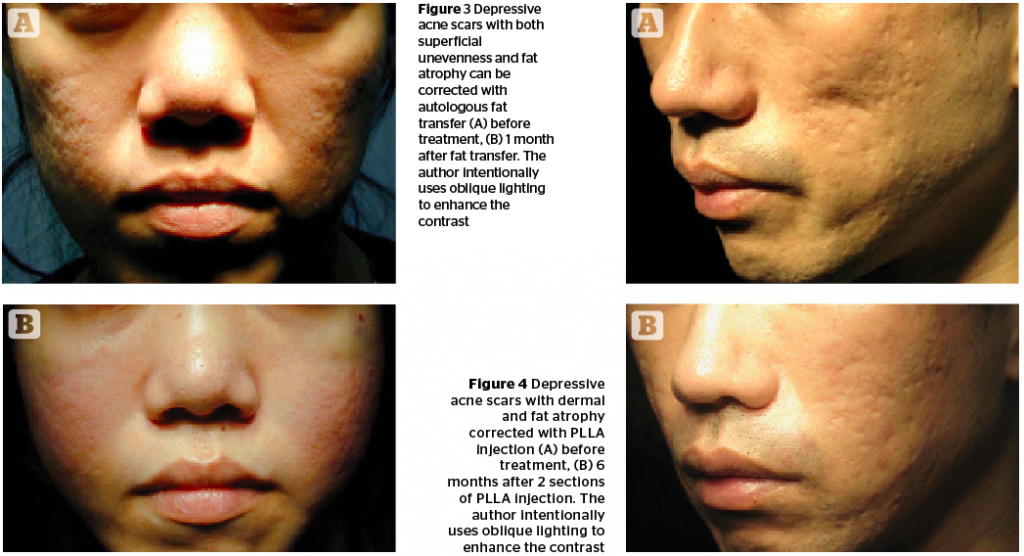

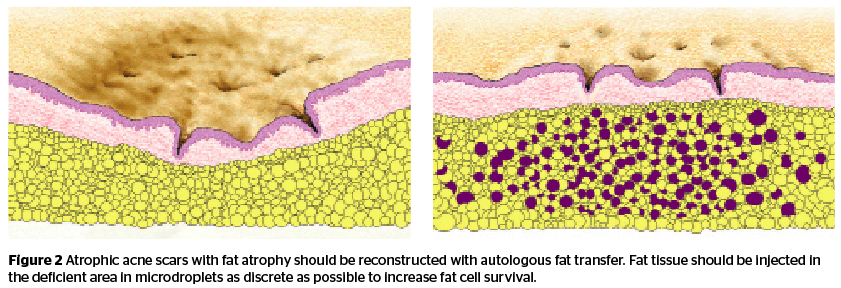

Autologous fat tissue transfer

When the loss of volume is subcutaneous fat, superficial and deep compartments could all be involved. Autologous fat transfer is simple, quick, and easy and the results can last for a long time. It is the treatment of choice to restore volume deficiency in the subcutaneous layer31. However, scarring tissue has inferior conditions of circulation to support fat survival and a difficult structure to accommodate fat cells. When performing a fat transfer to correct lipoatrophic acne scars, doctors have to put fat cells in microdroplets as tiny and as discrete as possible, and to put fat tissue in only atrophic areas to avoid puffing up the surrounding tissue that may enhance the contrast and further worsen the problem.

Soft tissue filler injection

Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA-collagen, Bellafill, Suneva), is a permanent filler recently approved by the US FDA for acne scar correction32. When injected superficially, PMMA can fill dermal volume deficits, and raise depressive tissue. PMMA is good for shallower, distensible scars with obscure margins. But for more fibrous scars and those with sharper margins, the placement of PMMA filler below the only decreases the magnitude of scar depression. For larger scales of tissue loss, PMMA should be carefully used to avoid the lumpy appearance contrasting the normal ageing curve or interfering with normal mimetic muscle movements33.

Poly-l-lactic acid (PLLA, Sculptra, Galderma, Fort Worth, TX) is an activating filler with clinical effects that can last for 25 months34. The injecting material needs to be reconstituted with distilled water 48 hours before injection. PLLA can induce immune reaction and self-tissue growth. When properly injected in tissue, the activated neo-tissue can fill volume deficits. PLLA filler thickens the skin, strengthens the skin structure, and improves the surface contour (Figure 4).

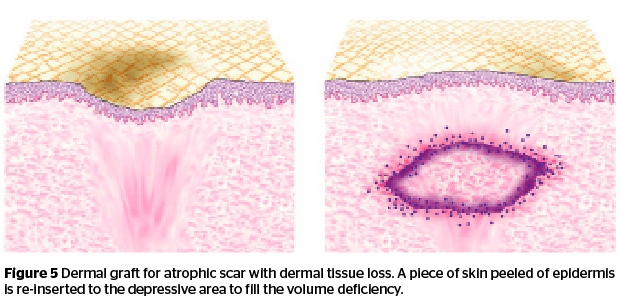

Dermal tissue grafting

When tissue loss occurs in the dermal layer, autologous tissue is another choice for long term correction35. A piece of dermal tissue can be harvested from the post-auricular skin.

The ideal scar for dermal grafting is a scar with intact epidermal contours but depressive due to dermal volume loss. The donor skin of the same size is trimmed to adapt the scar depression. The epidermis of the graft tissue is removed by scalpel. The recipient site is numbed with local anesthesia and dissected by an 18 G Nokor™ needle (1.5”, BD). Dermal graft tissue is then reinserted into the dissection-prepared pouch (Figure 5). Because some of the graft tissue will be resorbed, depression scars should be moderately overfilled.

Punch techniques

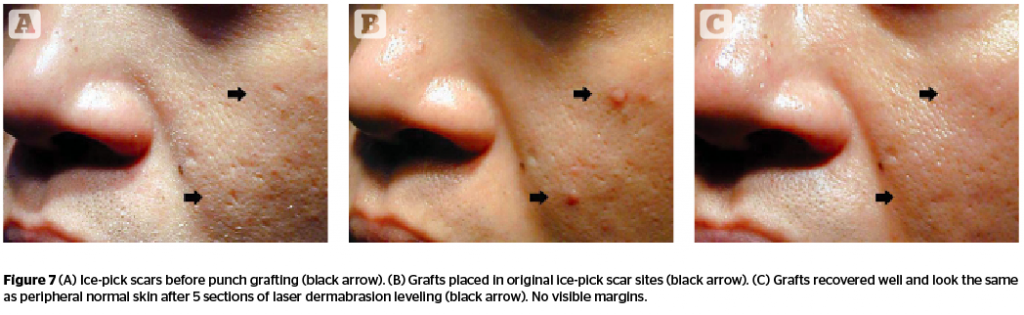

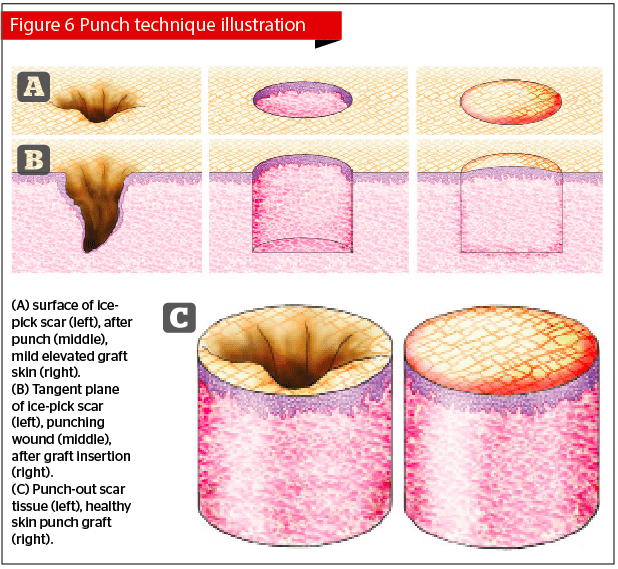

Ice-pick scars are the scars least responsive to dermabrasion and all other surface techniques. Most ice-pick scars are small in size, sharp in margins and deep. The wisest way to treat a tiny but deep scar is to preserve as much peripheral normal tissue as possible. Skin punches are small kits with sharp circular ends that are used for cutting tissue. These techniques using punches are referred to as punch techniques.

Punch grafting removes small sharp-margined atrophic acne scars. After the scar is punched out, the punching hole is then inserted with a piece of normal skin of similar size. Ice-pick scars should be removed by punches in assorted sizes according to the sizes of the scars in order to preserve as much normal skin as possible. The normal donor skin can be harvested most conveniently from the post-auricular area. The tiny grafts are fixed in the holes for one week. When grafts survive in their new location (Figure 6), the original depressions turn into flesh-colored papules. Grafted skin tends to pop out because of skin tension, but will gradually turn to even after repeated laser ablation (Figure 7).

Punch elevation

During the process of punching, blood accumulates between the free-floating scarring skin that is partially attached to the underlying tissue and the peripheral normal skin. The weak connection itself is distensible and it will appear that the ‘floating’ scar tissue was elevated after punching. However, the transient ‘floating’ of scarring tissue is only temporary. The whole process of punching results in no tissue gain. Even the ‘floating’ tissue is fixed with tape to maintain the flattening effect; after the blood is resorbed, the tissue will contract and return to its original state. The author personally views punch elevation as non-effective.

Punch excision

Many articles on acne scars mention punch excision. Punching is a good idea to preserve normal tissue. However, punch grafting is a fairly complicated procedure when you consider the techniques of graft tissue harvesting, preparation, size matching, controlled bleeding, graft trimming, matching of thickness, placing them evenly, fixing them securely, sculpting the surface, and blurring the margins. Compared with punch grafting, punch excision is much easier. Punch biopsy is an intern technique. All that needs to be done is punch out the tissue, then suture it. But when applying it in acne scars, it is completely different.

Ice-pick scars are rarely solitary. They and the surrounding tissue are usually tightly bounded by fibrous scars and less distensible. Even with punch biopsy, it is easy in technique but not good enough in practice. Forcing a circular tissue defect into a linear closure solely by the force of single stitch usually results in ugly stitch marks. The hole tends to turn back to its original circular shape and usually leaves a fusiform gap after healing. Both ends of the linear closure have to confront the forces of severe tissue distortion. They usually pop into dog-ear elevations. Asian skin is usually thicker and stronger, less distensible when compared to Caucasian skin and usually present with worse results from this technique. When two punch excisions are performed in adjacent locations, the skin in-between would be pulled by both sides. Facial contour would be further distorted after multiple punch excisions. In the author’s opinion, punch excision is the worst choice among all acne scar surgeries, and should only be considered in patients with thin skin and when the scars are limited in number.

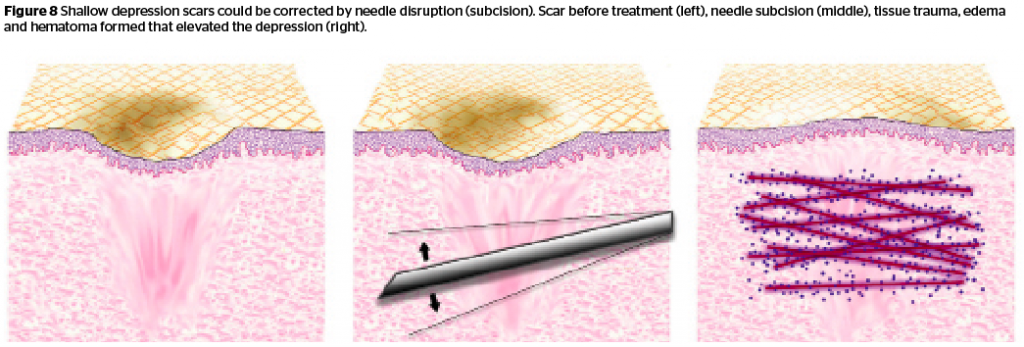

Subcision

Subcision is a technique based on the theory that scar depression originates from sub-scar fibrous tissue contraction. Traditionally, disruption of these fibrous bands with needles was regarded as possible in order to release these scars and restore them to a more even surface36. But the reason behind most scar depression is not fibrous tissue tethering but tissue loss. Scars themselves are fibrous tissue. Flatness achieved after subcision results from oedema and haematoma rather than tissue relief. Subsequent neo-scar formation elevates the depressive scars, too. Subcision should be considered when a patient has a limited budget, have scars with acceptable surface but only mild depression, and with scars larger and more numerous than the limit of punch techniques (Figure 8).

Frictional dermabrasion

Dermabrasion using a mechanical technique is more effective than laser dermabrasion because there are fulcrums to help doctors judge or adjust the level of tissue ablation. Dermabrasion itself is a process of tissue removal. The whole process results in a net tissue loss rather than tissue gain. Though wounded tissue would regenerate and contract after abrasive damage, tissue regeneration cannot grow beyond its original borders unless it is a hypertrophic or a keloid scar.

Chemical cauterization

Tissue damage and tissue regeneration after chemical cauterization is similar to the damage made by lasers or mechanical forces. Acids work more permeably by diffusion between tissues. Combination with CO2, mechanical abrasion or different chemicals together further enhances the chemical penetration.

Medium to deep chemical peels that blunt the margins of depressive scars and tighten the skin are beneficial for acne scars38. Superficial peel improves skin quality and color and helps the skin look better39.

Conclusion

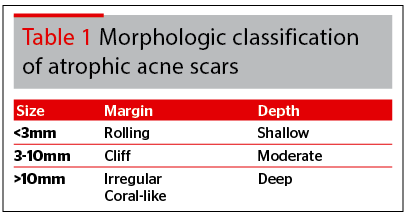

Acne scar surgery is a complex division of dermatologic surgery. Different scars should be considered and treated differently. Acne scars are usually a combined problem of volume change and surface unevenness. Effective acne scar treatment should cover volume correction, skin quality/texture enhancement and skin surface sculpting. Facing more choices of acne scar procedures, the traditional classification of ice-pick, rolling, and boxcar40 may not be enough. The morphologic classification system of acne scars needs to be more specified and correlate more with our treatment plan. The three dimensions of scar depth, size, and the style of scar margin might be more sensitive for guiding the treatment algorithm (Table 1). Smaller scars (<3mm) are more suitable for punch grafting. Atrophic scars with moderate size (3–10 mm) usually need dermal volume augmentation, while larger scars (>10 mm) might need fat layer augmentation. Scars with rolling margins can only be treated with volume augmentation, while scars with uneven margins need surface sculpting or scar tissue removal (full thickness grafting or excision). Atrophic scars deep in depth need fat layer volumization, while shallow scars might possibly be treated with only fractional, ablation levelling or tightening techniques.