Shino Bay Aguilera, Alec D McCarthy, Elina Theodorakopoulou, Saami Khalifian, Kelly McMahon, Saranya P Wyles, Doris J Day, Sabrina Ghalili, and Patricia Ogilvie examine the relationship between psychological and physiological ageing and the role of the aesthetic physician

The word ‘beautiful’ is an adjective that we often associate with something we like. According to Hesiod, an ancient Greek poet in the 6th century BC, the chorus of the muses suggested: ‘Only that which is beautiful is loved, that which is not beautiful is not loved.’ Aesthetic medicine focuses on the subjective nature of beauty itself. It also aims to address what many people fear: unattractiveness. Attractiveness is deeply ingrained in our survival instincts and desires1,2. Humans are naturally communal beings, as procreation and belonging are important elements of group dynamics. Therefore, we need to feel that we are able to attract a mate and be attractive to a group. Attractiveness is closely associated with the survival of individuals and species. Biologically, we are designed to identify signs of reproductive health and fitness in one another for procreation and protection3,4.

However, the physiological and subsequent psychological effects of chronological ageing are inevitable. Chronological and environmental ageing result in architectural changes across tissue planes (i.e., skin, fat, muscle, and bone) that alter the ratios and proportions of an otherwise youthful face5. As we age, our epigenome, or molecular factors that control gene expression, begin to deteriorate, and unlike genetic insults, epigenetic changes are reversible through lifestyle modification6. If left unaltered, ageing is a progressive phenomenon. Aesthetic providers have the ability to interrupt this physiological process with procedural, injectable, and topical treatments. While most aesthetic treatments primarily address phenotypic changes in patients, there are likely significant positive associated psychosocial changes as well7,8. In essence, aesthetic treatments may help improve poor self-perception and/or depression, which may manifest as improved ageing.

Two hypothesised mechanisms may be at play in helping individuals feel and behave younger. The first is psychological; it is based on how a person feels when they look in the mirror and see an appearance that is more in line with their perceived self-image and their desired youthfulness9. The second is biological; it may be associated with neurochemical changes in the brain when people have aesthetic treatments. Indeed, the positive impact of self-image on depression and other mental health disorders has been documented and implicated as a potential modulating target for aesthetic intervention10.

Recent studies have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of botulinumtoxinA injections in the glabella in improving depressive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder and other mood symptoms11. A randomised, observational clinical study looking at fMRI brain imaging before and after glabellar botulinum toxin injections showed decreased activity in the thalamus, suggesting a modulatory role on brain activity12. A possible confounder would be that decreased motor input from frowning may decrease thalamic activity. Nonetheless, patients treated with botulinumtoxinA in the glabella had a decrease in depressive symptoms that manifested as improved quality of life and improved mental health outcomes. To summarise the increasing body of literature connecting aesthetics and psychology: self-perception can impact mental health. Addressing aesthetic concerns in patients improves their self-perception and, in turn, their psychological state of mind.

While these concepts may be somewhat intuitive, their importance was thrust to the forefront during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The ‘Zoom Boom’ led to widespread video calling, which suggested that the more time someone spends analysing their own appearance, the more inclined they were to receive aesthetic treatments13. Similarly, during COVID-19, interest in aesthetic procedures, weight loss, and dieting increased14–16. At the same time, rates of depression and social media usage also increased17,18. The correlation between increased self-observation and aesthetic procedures may be explained by the interconnectedness of self-image and psychology.

Exploring trends

We performed a simple analysis on Google Trends, probing temporal and regional changes on self-image.

Google Trends is a publicly-accessible online tool that temporally and geospatially analyses a percentage of Google web searches. Search interest is reported as relative search volume (RSV) and reflects the quantity of searches for a particular term relative to the total number of searches carried out on Google and has been used frequently in healthcare to predict or analyse public interest trends13,14,19,20. RSV is scaled from 0–100 and is not a reflection of absolute search volume. Assessing relative searches is valuable for evaluating social trends, especially between search phrases. Up to 5 terms can be searched relative to one another. Further, geospatial data, which is reported as the average RSV over the given timeline, sheds insight into the regionality of a particular social phenomenon. Overall, Google Trends allows clinicians and researchers to assess and compare social interest in trends, terms, procedures, and thought processes, both independently and relative to other search phrases over defined time intervals and geographies. While no demographic data of searchers is procured, Google Trends also includes related search queries and topics. Related queries and topics are defined as terms or topics searches also searched for (in addition to the primary word or subject being analysed).

Results

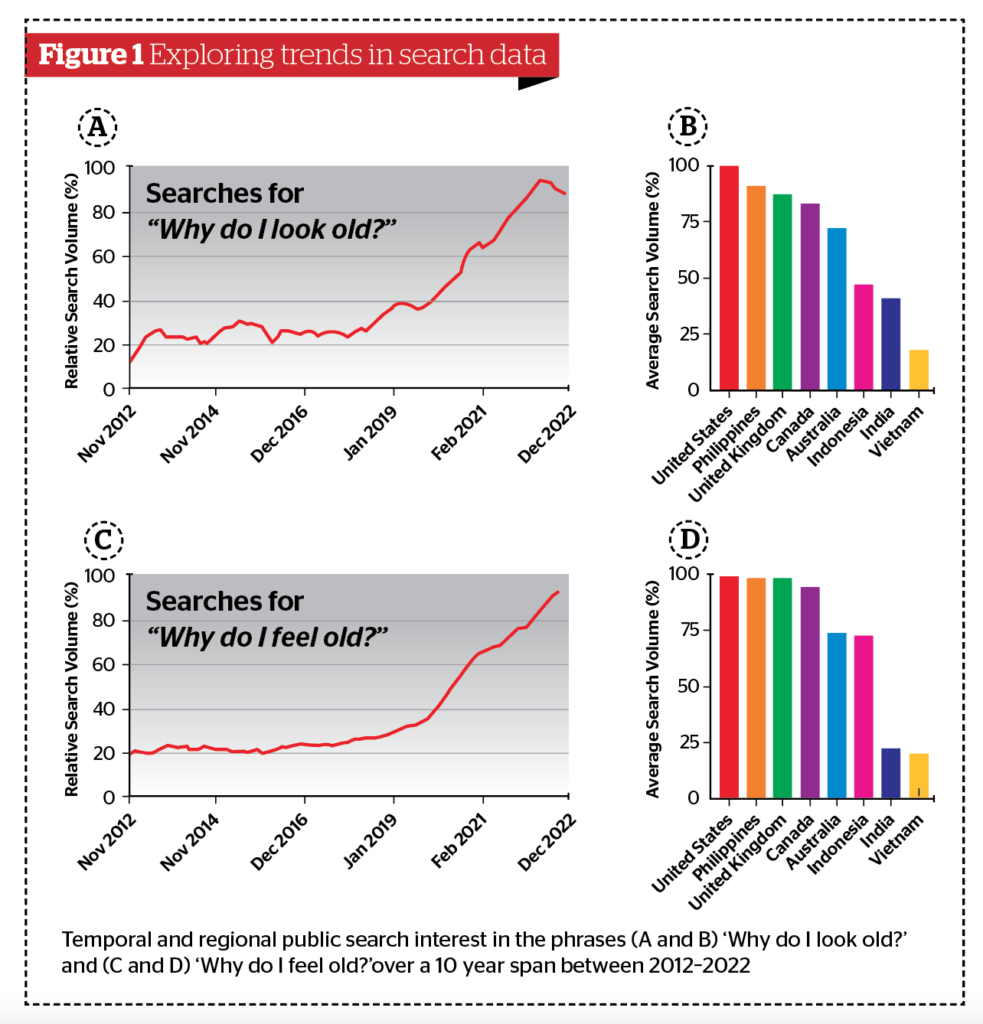

In this study, a panel of researchers and healthcare providers working in dermatology and aesthetic medicine procured a list of searches to be investigated. The following phrases were selected for social analysis: ‘Why do I look old?’ and ‘Why do I feel old?’. The temporal data was smoothed with a second-order smoothing polynomial and plotted (Figure 1 A and C). The geospatial data was plotted with bar graphs (Figure 1 B and D). The global map incorporates a colour gradient, where darker colours correlate with higher RSVs. Finally, related search queries were included to contextualise changes in search volume. Results suggest an increase in searches for ‘why do I feel old?’ over the past 10 years (2012–2022), including a significant increase in the rate of change starting in 2020, following the COVID-19 pandemic. This pattern was also highly correlated with searches for ‘why do I look old?’ thus implying a relationship between looking older and feeling older. The observed trend was not defined to a distinct geography as psychosocial aspects of ageing permeate across global borders, ethnicities, and cultures. However, the United States, United Kingdom, Philippines, and Canada were among the top search countries for both phrases.

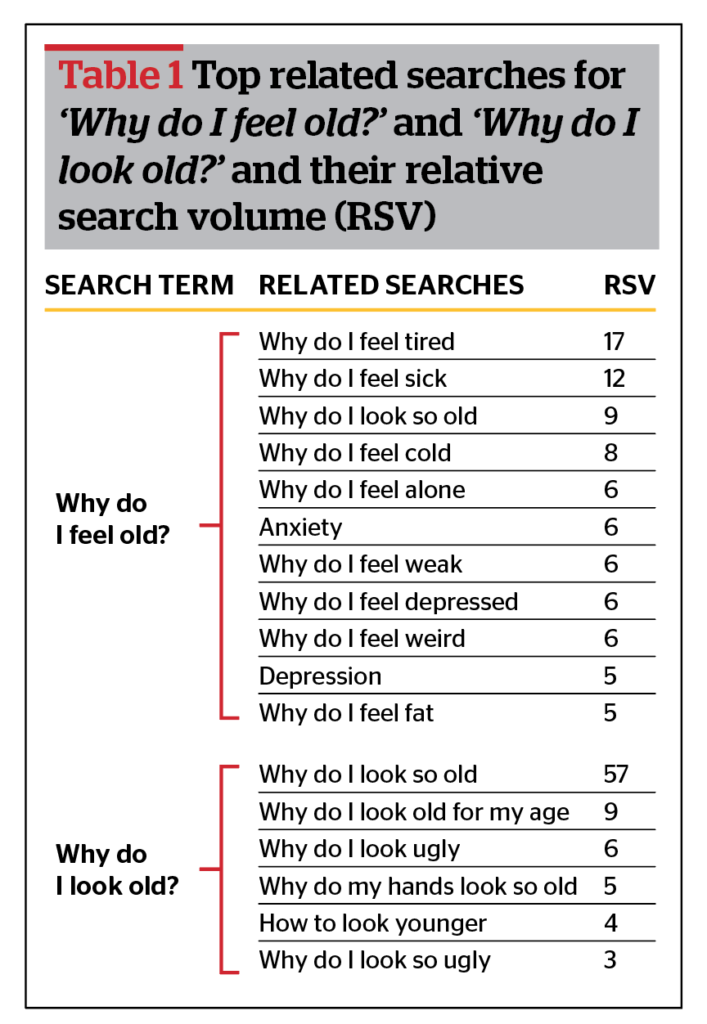

Another interesting observation from this simple analysis was in top/rising related queries. Several top related searches stood out to the authors: ‘Why do I feel tired?’, ‘Why do I feel sick?’, ‘Why do I feel alone?’, ‘Why do I feel empty?’, ‘Why do I feel depressed?’ were all related search terms tied to people searching ‘Why do I feel/look old?’ Select top related searches are given in Table 1.

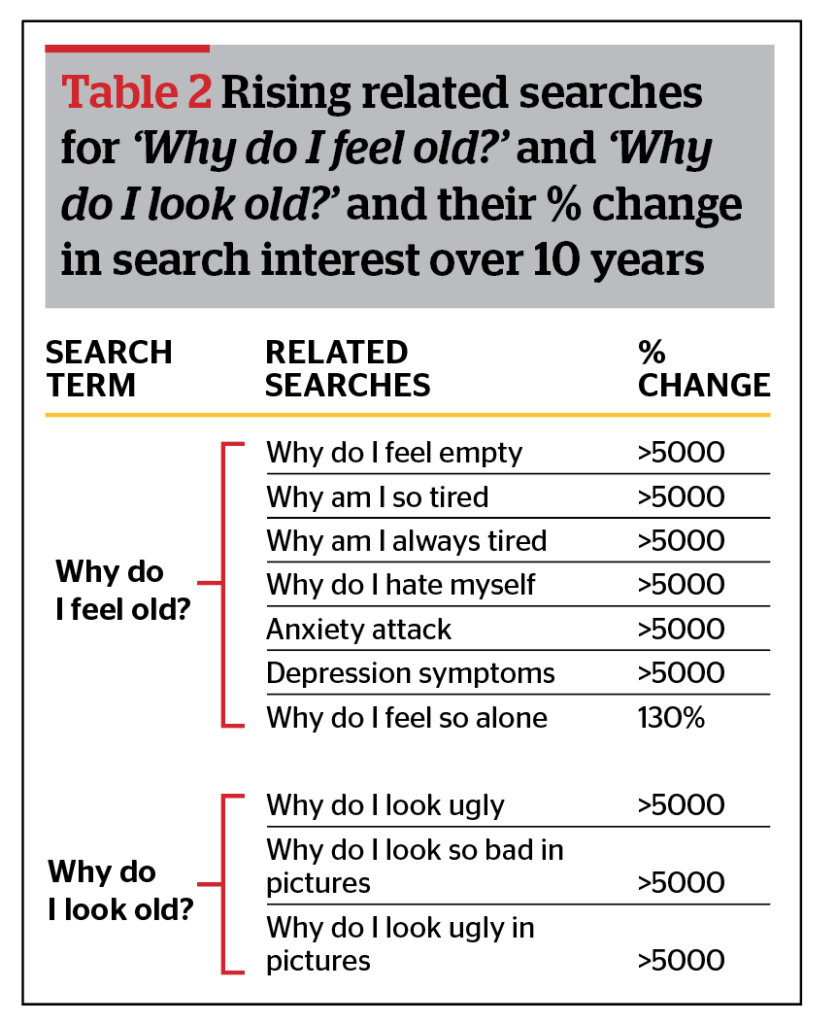

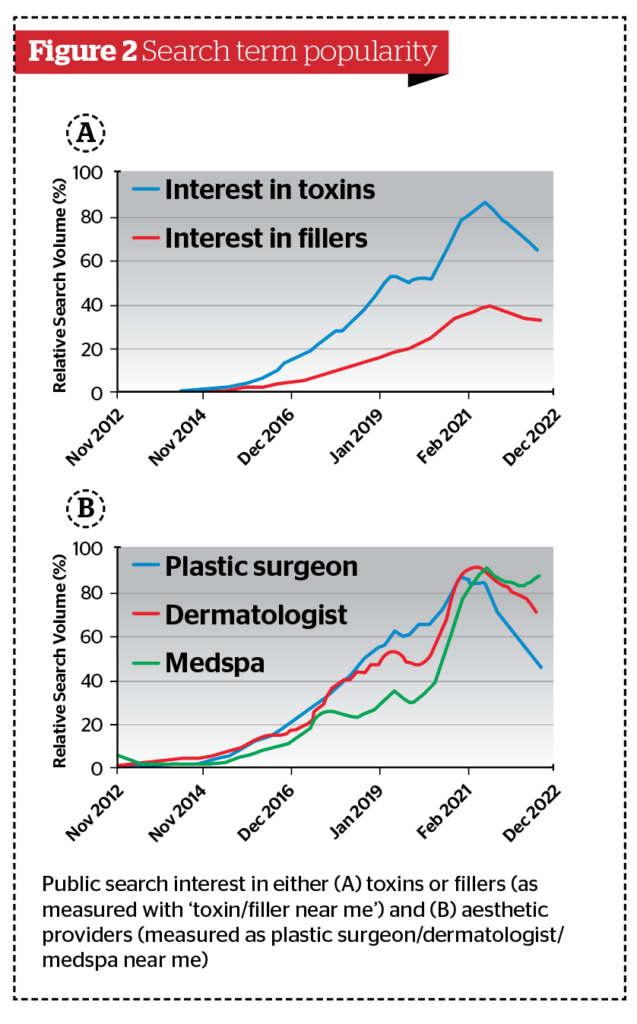

Similarly, rising related searches (those with the most significant changes over the time interval explored) are also provided. These perhaps shine the most light on emerging trends related to perceptions of ageing. Select rising related queries are presented in Table 2. Several rising phrases were ‘breakthrough’ searches (breakthrough results are those with more than a 5000% change over the time interval) and included ‘Why do I feel so empty’, ‘Why am I so tired’, ‘Why am I always tired’, ‘Why do I hate myself’, ‘Anxiety attack’, ‘Depression symptoms’, and ‘Why do I look ugly’. These related queries contextualise the dramatic changes in the observed psychosocial phenomenon: negative feelings/thoughts (psychological) and physical feelings of illness are related to increased negative changes in self-image. These findings support the notion that looking older and feeling older are related and carry with them a host of negative feelings and symptoms. Further, interest in dermal fillers and botulinumtoxinA have experienced dramatic increases in public interest that further correlates to searches seeking plastic surgeons, dermatologists, and medspas (Figure 2 A and B). The increased efforts by the general public to identify aesthetic providers for consultations or treatments is likely reflective of the positive changes in the perception of aesthetic treatments and also of a larger portion of the public desiring treatments.

The role of aesthetic medicine

The results from our analysis largely support the notion that aesthetic providers have the ability to not only address aesthetic concerns but also improve the mental health of patients. The downstream effects of which may be both psychological and physical. Aesthetic providers have the unique opportunity to identify insecurities that can lead to distorted self-perceptions and heal patients by treating their individual beauty concerns, which can be applied across all genders, age groups, and backgrounds. The notion of beauty is constantly reinforced to patients, and every provider should take an approach to assess both aspects of psychosocial ageing.

There has been an aim to promote positive perceptions of ageing in young and old individuals alike — which is where aesthetic medicine conveys its value to patients and the global healthcare system. Cosmetic procedures by trained aesthetic providers may improve physical beauty with the intention of manifesting positive general well-being. A large longitudinal survey of 8,434 participants found that greater facial attractiveness (as well as lower BMI and greater height) was associated with higher psychological well-being and a lower risk of depression21. Indeed, positive psychology can be beneficial in overall disease prevention, and aesthetic medicine is a field that aims to support this mentality. Ageism directly impacts the healthcare system from a cost perspective. A study of Americans aged 60 years and older revealed that the 1-year cost of ageism (in relation to discrimination aimed at older people, negative age stereotypes, and negative self-perceptions of ageing) was $63 billion, or 1 of every $7 dollars spent on the eight most expensive health conditions in 2013. The highest ageism predictor accounting for $33.7 billion dollars of the total cost was negative self-perceptions of ageing22. Another longitudinal study of 85,225 adults revealed that within a 5-year timeframe, individuals with high or increasing life dissatisfaction were significantly associated with higher healthcare utilisation costs23. A cynical attitude towards the future is financially draining the healthcare system today, and measures to combat this can have patient- and society-wide benefits.

Conclusion

Science increasingly favours the co-localisation of the mind and body connection and its effect on overall well-being. Our thoughts, emotions, and mentality can elicit an array of symptomatology, promoting either ease or dis-ease within the body. Ageing in itself is a disease where the body deteriorates at a rate relative to intrinsic and extrinsic stressors. Several studies support the theory that self-perceptions of ageing have a direct impact on overall health and well-being from an individual standpoint to the global healthcare system. Aesthetic medicine, occasionally considered a non-essential specialty, contributes to positive perceptions of ageing and therefore benefits both society and the medical community in the contemporary era of prolonged lifespans. Research has supported that both positive and negative age stereotypes can have beneficial and detrimental effects, respectively, on various physical and cognitive outcomes24. Furthermore, American culture subliminally fosters a cynical view of prolonged lifespans. On the contrary, if our thoughts can make us sick, they also have the power to make us well. Our data suggest a steady increase in negative changes in self-perception, which were linked to symptoms of psychological and physiological illnesses like anxiety and feelings of loneliness. This data further warrants the long-term need for aesthetic providers to improve patient self-perception. An ideal aesthetic provider should manage the ageing process for a patient and, in addition to meeting their aesthetic needs, help to bring positive mental changes that can result in a beautiful, productive, and meaningful life with patients achieving successful physical and psychological ageing.

Declaration of interest Dr Aguilera trains for/conducts research for Merz Aesthetics, Galderma,

References

- R. Brooks, Nature 2000, 406, 67.

- N. Nykodym, J. L. Simonetti, Journal of Employment Counseling 1987, 24, 69.

- J. A. Krems, S. Claessens, M. R. Fales, M. Campenni, M. G. Haselton, A. Aktipis, Nat Hum Behav 2021, 5, 726.

- M. Owen, Linacre Q 2013, 80, 17.

- G. W. Heinz, D. O. Kikkawa, International Ophthalmology Clinics 1997, 37, 1.

- S. Pal, J. K. Tyler, Science Advances 2016, 2, e1600584.

- J. E. Enabulele, J. O. Omo, African Journal of Oral Health 2017, 7, 1.

- S. Fagien, J. D. A. Carruthers, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2008, 122, 1915.

- Y. Jang, L. W. Poon, S.-Y. Kim, B.-K. Shin, Journal of Aging Studies 2004, 18, 485.

- J. Dainer-Best, J. D. Shumake, C. G. Beevers, Behaviour Research and Therapy 2018, 111, 72.

- A. ZAMANIAN, A. GHANBARI JOLFAEI, G. MEHRAN, Z. AZIZIAN, Iran J Public Health 2017, 46, 982.

- A. Hennenlotter, C. Dresel, F. Castrop, A. O. Ceballos-Baumann, A. M. Wohlschläger, B. Haslinger, Cerebral Cortex 2009, 19, 537.

- T. D. Pikoos, S. Buzwell, G. Sharp, S. L. Rossell, Aesthetic Surgery Journal 2021, 41, NP2066.

- J. D. Tijerina, S. D. Morrison, I. T. Nolan, M. J. Parham, R. Nazerali, Aesthetic Surgery Journal 2020, 40, 1253.

- C. P. Bellaire, J. W. Rutland, F. Sayegh, R. R. Pesce, J. D. Tijerina, P. J. Taub, Aesthetic Surgery Journal 2021, 41, NP2034.

- A. D. McCarthy, D. McGoldrick, Cureus 2021, 13, DOI 10.7759/cureus.15715.

- O. Renaud-Charest, L. M. W. Lui, S. Eskander, F. Ceban, R. Ho, J. D. Di Vincenzo, J. D. Rosenblat, Y. Lee, M. Subramaniapillai, R. S. McIntyre, Journal of Psychiatric Research 2021, 144, 129.

- J. Brailovskaia, J. Margraf, Computers in Human Behavior 2021, 119, 106720.

- A. D. McCarthy, D. J. McGoldrick, P. A. Holubeck, C. Cohoes, L. D. Bilek, Cureus 2021, 13, DOI 10.7759/cureus.16379.

- M. Eggerstedt, M. J. Urban, R. M. Smith, P. C. Revenaugh, Facial Plastic Surgery & Aesthetic Medicine 2021, 23, 397.

- N. Datta Gupta, N. L. Etcoff, M. M. Jaeger, J Happiness Stud 2016, 17, 1313.

- B. R. Levy, M. D. Slade, E.-S. Chang, S. Kannoth, S.-Y. Wang, The Gerontologist 2020, 60, 174.

- V. Goel, L. C. Rosella, L. Fu, A. Alberga, Am J Prev Med 2018, 55, 142.

- B. Levy, Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2009, 18, 332