Alexander Z. Rivkin, MD, unveils his Universal Injection Safety Precautions (UISP) that aim to ensure injectors can perform non-surgical rhinoplasty safely without compromising on results

Whereas the injection of fillers is a relatively safe procedure, adverse events (AEs), including serious ones like vascular compromise and ischemic complications, do occur. Complications from filler injection can occur anywhere on the face, but the nose poses a higher risk than anywhere else. The continuing rise in popularity of non-surgical rhinoplasty (NSR) demands that injectors develop a firm understanding of needed safety precautions so that outcomes are not only elegant and beautiful but also safe.

Injection safety in the nose hinges primarily on preventing and managing ischemic complications. Although bruising, erythema, tenderness, and swelling may occur, these are transient and treatable with over-the-counter medication and vascular lasers. In addition, moderately serious AEs like granuloma and delayed onset nodule formation that occur with filler injection in other areas of the face have not been reported after using US FDA-approved fillers in the nose1.

Overall, the principles that govern safe injection in the face can be applied to ensure safety in NSR; however, following those principles meticulously is of paramount importance with nasal injections. The nose is the most dangerous area in the body to inject with filler, and complications can be catastrophic. There are numerous reviews and reports of filler-related blindness and tissue necrosis, which illustrate this point all too well2. Injectable filler vascular complications happen when the tip of the needle or cannula is inside an artery, and a large amount of material is injected under high pressure, obstructing critical blood supply to the skin or the eye. The only exception to this rule is in the tip of the nose or the alar area, where ischemia can occur because too much filler compresses the small vessels in a tight space, causing a compartment syndrome-like effect. Preventing complications, therefore, hinges on preventing the confluence of these factors.

Is there a way to make sure that the tip of the needle or cannula is not inside an artery?

Unfortunately, the short answer to that question is — no. Until ‘smart’ needles that provide some signal upon passage into a blood vessel are widely available, we will be inherently injecting blind. Although aspiration is a widespread practice, there is no definitive evidence showing effectiveness in preventing complications. In fact, there is a growing consensus among expert injectors that aspiration is not only unreliable but actually decreases safety3,4. It is unreliable because the test is only assessing the exact spot where the tip of the needle is located during aspiration, not necessarily where the product is injected. This manoeuvre assumes that the injector’s hand has remained perfectly still through the performance of aspiration and subsequent injection. If the tip of the needle moves, even by a millimetre, the test is rendered useless. As demonstrated by a recent ultrasound study, it is physically impossible to aspirate a viscous gel, like those used for facial filling, without moving the tip of the needle several millimetres during the procedure4,5. Considering the size of the vessels to be avoided, this distance is clearly far too large to assure safety during product placement. Of note, some have argued that aspiration without motion is possible if the needle is resting on bone. While this may be true for a brief suction time, it is very unlikely true for the extended times suggested by the aspiration literature as necessary for a reliable test, especially when using the highly viscous fillers needed for good NSR outcomes6. False negative findings with aspiration are common enough7,8 to suggest the practice itself creates a false sense of security for injectors, which could lead to the placement of large amounts of filler under high pressure inside a patient’s artery. Until technology provides a way to detect arterial puncture, one must inject assuming that their needle or cannula is always inside a vessel.

If we cannot control needle location, how do we inject safely?

Before discussing techniques to improve safety, it is important to dispel the myth that an expert level of anatomic knowledge reduces injection risk to zero. Anatomy will indicate the areas or depths that are relatively higher or lower risk; however, individual variability in the course and depth of facial vessels is such that one can never be certain that a given area or plane of the face is completely safe. Fang et al. recently published an article describing positive aspirations at all depths, including the supra-periosteal plane9.

If we cannot know whether a needle is in a vessel, what can be done to ensure safe injection?

Though there are no randomized clinical trials on the subject, there are evidence-supported practices which can reduce risk. First, one must do everything possible to limit the volume of filler deposited in any one injection point. Because one must assume that the needle tip is always in a dangerous place, injecting a large bolus filler is an unsafe practice under any circumstance. Admittedly, this stance is in contrast to many of the recommendations and techniques popular today, and it is not uncommon to read claims that bolus injections on periosteum or perichondrium are ‘safe’. The literature on anatomic variability, however, provides clear evidence that doing so is unwise. Given the absence of any true ‘safe plane’ for injection, and the stakes at hand, it is best to take appropriate precautions. The sections below describe a set of protocols developed by the author, Universal Injection Safety Precautions (UISP). These principles should be applied in combination with adequate training and knowledge of anatomy.

Universal Injection Safety Precautions (UISP) relevant for all treatment areas

- Continuous retrograde motion as filler is moving through the needle. Constant motion limits the amount of filler deposited in any one place to a very small amount. This practice is more reliable than aspiration because, even if the needle is inside a vessel, it will exit the vessel before enough material has been deposited to cause an AE. If the injection is placed as a vertical column, this practice also improves tissue lift because expanding multiple tissue planes leads to more efficient and precise projection.

- Slow, low-pressure injections give the injector time to react if early signs of ischemia present. This type of injection also will not overcome systolic blood pressure, which is required for a filler to move retrograde through an artery.

- Injectors should use the smallest gauge needle possible. A small needle gauge encourages small injection volumes and enhances patient comfort. Cannulas should be 25 gauge or larger. Sizes smaller than 25G can pierce vessels, but this must be balanced against the fact that larger cannulas can compromise precision, which is especially important for good outcomes in the nose.

- Diligent cleansing of the skin with alcohol, chlorhexidine or hypochlorous acid is important because the fillers can remain under the skin for several years. We want to prevent the formation of an environment likely to harbor chronic infections.

Universal Injection Safety Precautions (UISP) specific to non-surgical rhinoplasty

- Ice the skin of the nose prior to injection. This will shrink the vessels and decrease the risk of perforation. One exception is patients who have had rhinoplasty in the past, as their dermal blood supply is already compromised. For these patients, icing may increase the risk of ischemia.

- Use 0.3 or 0.5 cc insulin syringes backloaded with filler. These syringes come with smaller needles (28 to 31 gauge) and permit the precise deposition of tiny (0.01 to 0.03 cc) amounts of product. Insulin syringes improve safety by limiting the amount of product injected per spot. The outcome is improved because of an increase in precision. They also improve patient comfort. Aspiration is not possible with these syringes due to needle size and syringe construction.

- Additional suggestions to improve safety for nasal injections include:

- Place most injections at the midline, as the major vessels of the nose mainly run on the lateral aspects. That being said, there are vessels in the midline, and anatomic variability dictates that some people will have a dorsal nasal artery which runs down the middle of the dorsum. Thus, careful adherence to UISP rules is necessary, even in the midline. Of note, advanced NSR injectors will regularly inject outside of the midline, because correction of many asymmetries and cases of cartilage collapse require filling of the nasal sidewall.

- Pinch compress the dorsal nasal and supratrochlear vessels during radix injection to prevent inadvertent cannulation.

The goal of UISP and the other effective safety precautions is not to prevent our needle or cannula from entering a vessel. We enter vessels all of the time when we inject filler, as is obvious from the frequency with which we cause bruising. The goal is to make sure that, no matter where the tip is, we never inject enough filler to cause an ischemic AE.

Which patients are most at risk from complications with NSR?

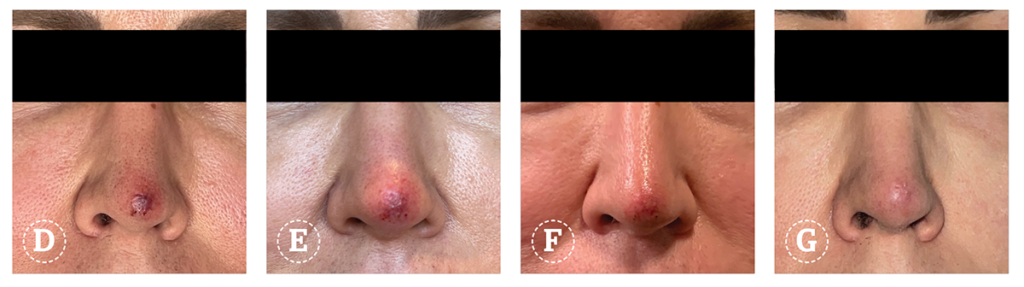

In a retrospective review of my first 2400 NSR cases, patients who had undergone previous rhinoplasty surgery had a 50% higher risk of AEs10. Blood supply to the nasal skin of a post-rhinoplasty patient is inherently compromised, increasing the risk of compressive ischemia and necrosis. Post-operative scar formation can fixate vessels, limiting their ability to roll away from a needle or cannula and thereby increase the risk of an embolic event. These patients should only be treated by the most senior NSR experts, and particular precautions should be implemented both pre- and post-injection.

Of the nasal subunits, we found that the tip, sidewall, and alar areas had the highest frequency of adverse events. Of note is that our analysis included minor adverse events such as prolonged erythema, tenderness, and ischemic AEs. The increased risk at the tip and alar areas are most likely due to the relative lack of redundant blood supply in these areas, as well as the relatively small and tight potential space due to the disordered arrangement of fibrofatty tissue and muscle. Unlike the rest of the nose, the tip, ala, columella and radix do not have a classic five-layer structure. The increased risk at the sidewall is due to the presence of large vessels, such as the angular and dorsal nasal arteries and veins and their respective branches. These can cause significant bruising or embolic ischemia when perforated.

Which fillers are safest to use in NSR?

Every beginner- and intermediate-level NSR injector should use hyaluronic acid (HA) fillers exclusively for NSR. The reversibility of HAs is a critical safety advantage when injecting a high-risk area like the nose. Of the US FDA-approved HA fillers, JUVÉDERM® VOLUMA®, JUVÉDERM® Volux™ (Allergan, Irvine, CA, USA) and Restylane® Lyft (Galderma Laboratories, Irving, TX, USA) are best for NSR due to their longevity, low water absorption, and ability to project tissue. Viscous fillers like these are relatively more cohesive and, therefore, able to hold their shape and avoid spread over time. This quality is essential for sculpting tip-defining points, dorsal edges, and performing the kind of precise contour adjustment necessary for successful NSR. After many years and thousands of patients, I have incorporated poly methyl methacrylate — collagen gel (PMMA, Bellafill; Suneva Medical, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) for NSR. Most patients choose to do one session of HA for the peace of mind that reversibility confers and to be certain of satisfaction with the results. At the recommended touch-up session, however, they have the option of switching to PMMA. Every patient is informed of the risk of using a non-reversible filler and the inadvisability of having rhinoplasty surgery at any point after PMMA injection. In my experience, PMMA is an effective filler for NSR with an unmatched duration of effect and an excellent safety profile if injected in the deep dermal to subdermal layer under UISP11.

Fillers not recommended for use in the nose include:

- Silicone. This material was used extensively in the 1980s but was abandoned because of devastating inflammatory reactions. A few expert injectors use a microdroplet technique effectively in the nose for carefully selected patients, but the material itself is accompanied by too much risk for broader use.

- Calcium Hydroxyapatite (CaHA; Radiesse; Merz Pharmaceuticals GmbH, Frankfurt, Germany). Despite a superior G’ (a measure of stiffness), CaHA duration of effect in the nose is quite variable once the carboxymethyl cellulose carrier is absorbed10. Given this limitation, the negative impact of irreversibility on the safety profile makes NSR injection with this filler undesirable.

- Other poor choices for NSR include soft and/or hydrophilic HA fillers, fat, and poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA [Sculptra, Galderma, Irving, TX, USA]). These agents are not able to lift tissue sufficiently and tend to spread and swell after injection, giving unpredictable and poorly defined NSR results. Additionally, fat and PLLA are not reversible.

What should I do if I suspect an ischemic event?

The safe performance of NSR hinges on a thorough understanding of adverse event prevention, as outlined above; however, there are additional requirements. The safe NSR injector must also be fully capable of recognizing and managing adverse events. The first sign of ischemia in the nose is often a painless blanching that is slow to resolve. If ignored, this can proceed to pain and mottled duskiness with slow capillary refill in the surrounding area. The competent NSR injector must be able to easily differentiate the solid, well-demarcated colour of a hematoma from the mottled appearance of ischemic livedo reticularis. They should also know exactly what to do if ischemia is suspected, with the understanding that timely action is the only way to prevent progression to necrosis. Steps to be taken immediately include:

- Stop injecting!

- Massage the area vigorously

- Apply heat in the form of a warm compress

- Give the patient 325mg of aspirin.

In over twenty years of experience with NSR at my practice, countless cases of early ischemia have been resolved in seconds when steps 1 and 2 above were performed immediately. Based on clinical experience, intense massage of the area for a minute or so appears to stop vasospasm and normalize blood flow, especially in post-surgical noses. Vasospasm accompanies and significantly complicates ischemia12. I believe that vasospasm often causes a feed-forward loop of ischemia and tissue damage that leads to necrosis if not resolved right away. If ischemia resolves with massage, a warm compress should be applied for 10 minutes, and a dose of aspirin should be given. If the area appears pink at this time, no further steps are necessary aside from the patient sending a photo of their nose in a few hours to ensure no delayed effects are manifesting.

If massage does not resolve blanching and/or the area in question looks dusky or mottled after the first compress, further measures should be instituted. The injector should have a ‘crash cart’ with all of the below emergency supplies easily accessible:

- Hyaluronidase. Inject with enough hyaluronidase to cover the entire surface area involved, not just the injection point. The usual dose in the nose for this situation ranges from 50 to 300 units or more. Repeat hyaluronidase treatment hourly until capillary refill and skin color normalize. This recommendation applies irrespective of the filler used.

- Nitroglycerin paste. Apply 2% nitroglycerin paste (NitroBid, Fougera, Melville, NY, USA) after hyaluronidase injection for 20 to 30 minutes. Although controversial, I have found this treatment to be beneficial. There is a theoretical concern that dilating vessels could worsen ischemia by permitting filler particles to move to smaller arterioles, but there is no empirical evidence to support this hypothesis, and I have not seen evidence of this happening in my patients.

- Steroids. Start a five-day steroid taper with the first dose administered in the treatment room. It is important to keep steroids on hand rather than providing a prescription. Patients may change their minds about taking steroids once they leave the office, a decision which could worsen outcomes.

- Nitrous oxide. If available, nitrous oxide should be administered via inhalation while the patient waits for hyaluronidase and nitro paste to take effect.

- Additional medication. Other medications that could also be helpful for increasing blood flow include sildenafil, tadalafil, and vardenafil.

If the patient’s skin improves after steps 1–5 are performed, they should be observed for fifteen minutes and sent home with instructions to take aspirin (325 mg bid) and use warm compresses, periodic massage, continued steroids, and nitroglycerin paste (one hour on, one hour off). The patient should send photos of the area every 12 hours and should return to the clinic for re-evaluation the next day. Hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) treatment should be instituted if there is any doubt that the skin will fully recover. The earlier HBO treatment is initiated, the more effective it is.

If the area in question does not improve despite all the measures taken, including HBO treatment, or if the injector is not notified before necrosis has set in (two or more days after the original injection), wound care protocol should be initiated. The skin should be kept well hydrated with topical emollients and dressings, antibiotics or antivirals should be considered, and the patient should be referred to a wound management expert for further care.

What if the patient has vision changes?

Every aesthetic practitioner must be aware and prepared for the remote but devastating possibility of injectable filler causing visual compromise. NSR injectors especially so, since the glabella and nose are well known to be the areas at greatest risk2. If visual compromise is suspected, the injection should cease at once, and the function of each eye must be immediately documented. NSR injectors should make sure they are practised at administering these tests quickly.

- Ability to read a Snellen chart

- Ability to read a newspaper or magazine

- Count fingers and perceive hand motion

- Extra-ocular motion

- Pupillary response to light evaluation.

If there are indications of stroke, such as unilateral weakness, severe headache, confusion, sudden speech difficulties or dizziness, the patient must be immediately transported to the nearest emergency room, and the rapid response stroke team must be alerted.

If stroke is not suspected, a retinal specialist should be summoned emergently. Each NSR injector should establish a relationship with a retinal specialist in anticipation of this possibility. In the meantime, the injector must act, as irreversible damage can occur within 15 minutes of the onset of visual symptoms. The practitioner should inject several hundred units of hyaluronidase into the area that was being treated, as well as into the supratrochlear and supraorbital foramina. Several hundred more units should be injected into the retrobulbar or peribulbar area. There is little concrete evidence to show that these injections work to reverse ischemic blindness, but the potential benefits far outweigh the risks13. Other techniques that may help include:

- Breathing into a paper bag can lead to carbogen dilation of the retinal vasculature

- Retinal massage. Gently pressing and releasing the eye twice per second for an hour or two may dislodge the emboli and improve vision14

- Topical Timolol and oral Acetazolamide. These medications decrease intraocular pressure and should be in every NSR injector’s crash cart.

Is it worth it to become an advanced NSR injector?

Non-surgical rhinoplasty is a life-changing procedure for patients. For this reason, although it is a complex and risky procedure to perform, it is immensely rewarding for the injector. The successful NSR injector must know the anatomy of the nose, be aware of nasal aesthetics (as well as important differences between ethnicities), and be an expert in the safe and effective use of all of the injectable fillers on the market. Safety must always be the first priority in the nose with diligent adoption of robust and evidence-based precautions, such as UISP, as well as thorough preparation for any and all adverse event possibilities.

- Declaration of interest Dr. Rivkin is a speaker and ad board consultant for Galderma, Allergan, Suneva Medical, and Merz; and a principal investigator for Allergan, Suneva and Galderma.

- Figures 1–2 © Dr. Rivkin

References

- Wang JV, et.al. Utility of preinjection aspiration for hyaluronic fillers: a novel in vivo human evaluation. J Cutan Med Surg. 2020; 24(4): 367- 371.

- Beleznay K et.al. Update on avoiding and treating blindness from fillers: a recent review of the world literature. Aesthet Surg J. 2019; 39(6): 662- 674.

- Rivkin AZ. Aspiration: I don’t do it and neither should you. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021 Apr;20(4):1042-1043

- Goodman GJ et.al. Aspiration Before Tissue Filler-An Exercise in Futility and Unsafe Practice. Aesthet Surg J. 2022 Jan 1;42(1):89-101.

- Lin F, et.al. Movement of the Syringe During Filler Aspiration: An Ultrasound Study. Aesthet Surg J. 2022 Sep 14;42(10):1109-1116.

- Kapoor KM et al. Factors influencing pre-injection aspiration for hyaluronic acid fillers: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Dermatol Ther. 2020;e14360.

- Torbeck RL et.al. In Vitro Evaluation of Preinjection Aspiration for Hyaluronic Fillers as a Safety Checkpoint. Dermatol Surg. 2019 Jul;45(7):954-958.

- Van Loghem JA et.al. Sensitivity of aspiration as a safety test before injection of soft tissue fillers. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018 Feb;17(1):39-46.

- Fang WT et.al. Descriptive Analysis of 213 Positive Blood Aspiration Cases When Injecting Facial Soft Tissue Fillers, Aesth Surg J, Vol 41, Issue 5, May 2021; 616–624

- Rivkin A. Nonsurgical Rhinoplasty Using Injectable Fillers: A Safety Review of 2488 Procedures. Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. 2021 Jan-Feb;23(1):6-11.

- Rivkin A. PMMA-collagen Gel in Nonsurgical Rhinoplasty Defects: A Methodological Overview and 15-year Experience. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022 Aug 19;10(8):e4477

- Murray G, et.al. Guideline for the Management of Hyaluronic Acid Filler-induced Vascular Occlusion. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021 May;14(5):E61-E69. Epub 2021 May 1.

- Jones, D et.al. Preventing and Treating Adverse Events of Injectable Fillers: Evidence-Based Recommendations From the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Multidisciplinary Task Force. Dermatologic Surgery 47(2):p 214-226, February 2021.

- Rommel F et.al. Evaluating Retinal and Choroidal Perfusion Changes After Ocular Massage of Healthy Eyes Using Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020 Nov 26;56(12):645.