3D bioprinted skin is advancing in studies with the potential to become a next-generation solution in aesthetics and regenerative medicine

Scientists in the U.S., South America, Europe, and elsewhere are in their labs studying how to create 3D bioprinted skin and other tissues that can safely and effectively improve outcomes in reconstructive surgery, wound healing, and other applications.

A bioengineering feat, bioprinting is expected to transform dermatology and aesthetic surgery over the next decade by enabling the creation of customised skin grafts, engineered tissues and even entire skin equivalents, says Viviane Abreu Nunes, PhD, an author of one of those recent studies and associate professor II at the School of Arts, Sciences and Humanities, University of São Paulo, in São Paulo, Brazil.

‘This will enhance treatment options for burns, scars, wounds, and age-related skin deterioration. In aesthetic practice, bioprinting could allow for patient-specific fillers or implants made from biocompatible tissue rather than synthetic materials, improving both safety and outcomes,’ says Dr Nunes, who is currently a visiting professor in the wound healing and regenerative medicine research program at the department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL, USA.

Dr Nunes led an international team of researchers publishing the paper ‘Advances in regenerative medicine-based approaches for skin regeneration and rejuvenation,’ in Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, looking among other innovations at biological skin substitutes.

‘These innovations aim to reduce morbidity from both acquired and congenital skin diseases, as well as replace or regenerate soft tissues lost or damaged due to ageing, injuries, scars, or wrinkles. The ultimate goal is to restore a rejuvenated, natural, and aesthetically pleasing appearance to the skin,’ the authors write.

Aesthetic and regenerative applications

Bioprinted tissue can be used for grafting in burns and chronic wounds, for reconstructive surgery following trauma or tumour removal, and potentially for aesthetic skin rejuvenation, according to Dr Nunes.

Surgeons, for example, could apply bioprinted dermal-epidermal composites directly to wounds, allowing for improved integration and reduced scarring, she says.

‘In the future, printed skin patches with embedded hair follicles, sweat glands, or pigment-producing cells may also be used for more complete functional and cosmetic restoration,’ Dr Nunes says.

Dino J. Ravnic, DO, MPH, MSc, professor of surgery, division of plastic surgery, Penn State College of Medicine, and co-authors recently reported in a study published in Bioactive Materials that fat tissue holds the key to 3D printing layered living skin and potentially hair follicles. The researchers harnessed fat cells and supporting structures from clinically procured human tissue to precisely correct injuries in rats. The patented bioprinting technology could have implications for reconstructive facial surgery and even hair growth treatments for humans, according to a Penn State press release.

In essence, the Penn State team created skin using stem cells, retrieving those stem cells from patients’ fat.

Stem cells have the ability to go into multiple tissue lines, as well as self-replicate and maintain their lines, Dr Ravnic explains.

‘So, you’re able to grow these stem cells in a petri dish with the appropriate nutrients … and they can expand themselves. Then, when you change the nutrients that they’re exposed to, you can differentiate them into skin or fat or bone or blood vessels. A whole slew of different tissue types,’ he says.

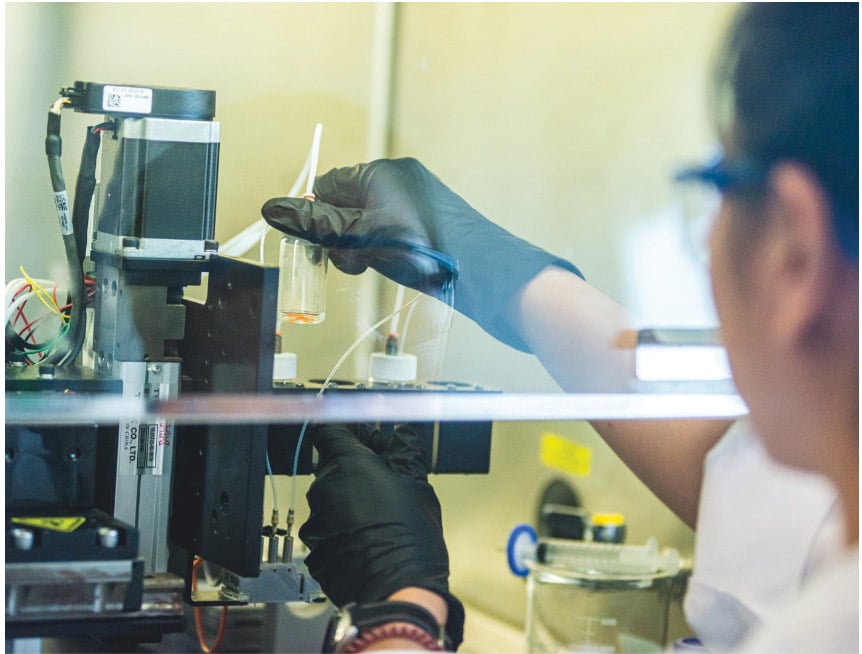

Researchers used this approach intraoperatively, printing the skin and applying it in the OR (albeit in an animal model). Theoretically, in human studies, clinicians would bring the bioprinter into the OR and use computer programming to design where the cells need to go.

‘The bioprinter usually has a number of different print heads, and you can deposit the kinds of cells—layer by layer and the type of cell that you want, exactly where you need it to be. We look at the area that we’re trying to rebuild in the operating room, and then, on demand, we basically build it. There’s no prefabrication. Everything is on the spot,’ Dr Ravnic says.

Again, theoretically, because it hasn’t been tested in humans, patients’ bodies would not reject bioprinted skin made with their own cells. But that remains uncertain.

Hydrogel is the medium of the bio-ink that cells are deposited in, says Dr Ravnic. In this case, the researchers created the hydrogel component by taking the extracellular matrix from adipose and using it to make a bio-ink.

‘We saw that when you source the stem cells and extracellular matrix, and you deposit it in a layer-by-layer fashion, you can also achieve some hair follicle growth,’ he says.

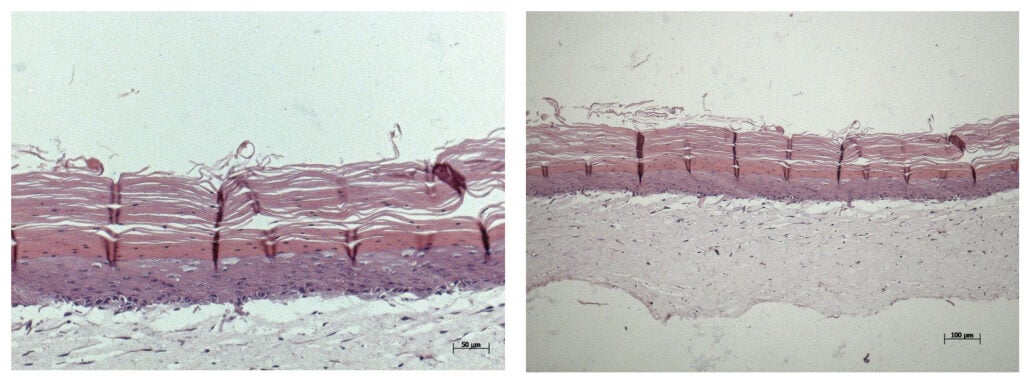

In three sets of rat studies, the researchers achieved the hypodermis and dermis layers, with the epidermis forming within two weeks, according to Ibrahim T. Ozbolat, PhD, professor of engineering science and mechanics, of biomedical engineering and of neurosurgery at Penn State, who led the study.

‘… we found the co-delivery of the matrix and stem cells was crucial to hypodermal formation,’ Dr Ozbolat said in the press release. ‘It doesn’t work effectively with just the cells or just the matrix — it has to be at the same time.’

They also found that the hypodermis contained downgrowths, the initial stage of early hair follicle formation. According to the researchers, while fat cells do not directly contribute to the cellular structure of hair follicles, they are involved in their regulation and maintenance, according to the Penn State press release.

‘In our experiments, the fat cells may have altered the extracellular matrix to be more supportive for downgrowth formation,’ Dr Ozbolat said. ‘We are working to advance this, to mature the hair follicles with controlled density, directionality, and growth.’

Next in this research, the team will study the approach in a sheep model, according to Dr Ravnic, who says this type of tissue engineering represents the next era of reconstruction.

Bioprinting nuances and differentiators

In their paper, Dr Nunes and colleagues mention droplet-based, laser-assisted, and extrusion-based bioprinting.

‘Droplet-based bioprinting is similar to inkjet printing. It ejects small droplets of bio-ink through a nozzle, usually using thermal or acoustic energy. It’s ideal for high-resolution, low-viscosity applications but limited in cell density,’ she says. ‘Laser-assisted bioprinting uses a focused laser to transfer bio-ink from a donor layer to the substrate. It’s highly precise and does not clog, making it suitable for delicate or high-density cell applications, though it is expensive and complex. Extrusion-based bioprinting pushes bio-ink through a nozzle using pneumatic or mechanical force. It’s the most commonly used method and can print high-viscosity materials and large volumes, but with less resolution than the other two.’

Common biomaterials that could go into making the tissue include collagen, gelatin, hyaluronic acid, alginate, and fibrin, all of which can be combined with patient-derived cells like fibroblasts and keratinocytes, according to Dr Nunes.

‘Synthetic polymers like PCL or PLA may also be used as scaffolds. While we’re not quite there yet, the concept of office-based bioprinting is plausible within the next decade, especially for small grafts or personalised tissue patches. Point-of-care bioprinters are already being prototyped for battlefield and emergency use, suggesting clinical scalability,’ she says.

Challenges to overcome

While exciting and promising, obstacles remain for translating bioprinted tissue to mainstream practice.

Key obstacles, according to Dr Nunes, include:

Regulatory approval: Bioprinted tissues must meet strict FDA and EMA standards for safety, efficacy, and reproducibility.

Vascularisation: Successfully integrating printed tissues with the patient’s circulatory system remains a major challenge.

Standardisation and cost: Protocols must be standardised for broader use, and bioprinters must become more affordable and user-friendly for clinical settings.

Training: Surgeons and clinicians will need training to operate bioprinters and handle living materials safely and effectively.

‘Despite these hurdles, integration into routine care is accelerating, especially in advanced wound care and aesthetic centres,’ Dr Nunes says.

For now, plastic surgeons engaging in regenerative medicine or wound care should understand the basics of tissue engineering, including cell sourcing, scaffold design, and the role of growth factors, according to Dr Nunes.

‘As bioprinting technologies evolve, familiarity with bio-inks and bioreactor systems will become increasingly relevant. To get started, clinicians can attend courses in regenerative medicine, join interdisciplinary conferences, and establish partnerships with academic or biotech labs that specialise in bioprinting,’ she suggests.

References

- Dutra Alves NS, Reigado GR, Santos M, Caldeira IDS, Hernandes H dos S, Freitas-Marchi BL, et al. Advances in regenerative medicine-based approaches for skin regeneration and rejuvenation. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. 2025 Feb 12;13.

- Kang Y, Yeo M, Derman ID, Ravnic DJ, Singh YP, Alioglu MA, et al. Intraoperative bioprinting of human adipose-derived stem cells and extracellular matrix induces hair follicle-like downgrowths and adipose tissue formation during full-thickness craniomaxillofacial skin reconstruction. Bioactive Materials [Internet]. 2024 Mar 1;33:114–28. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2452199X23003493?via%3Dihub

- 3D-printed skin closes wounds and contains hair follicle precursors | Penn State University [Internet]. Psu.edu. 2024. Available from: https://www.psu.edu/news/research/story/3d-printed-skin-closes-wounds-and-contains-hair-follicle-precursors

Written by Lisette Hilton, contributing editor

Figure 1 © Laboratory of Skin Physiology and Tissue Engineering of the School of Arts, Sciences and Humanities of University of Sao Paulo. Figure 2 © Michelle Bixby/Penn State. All Rights Reserved