Pierre J. Nicolau makes the case for cone sutures to address the tissue displacement that takes place in the ageing face

The first well-documented attempts to use suspension material in the face were by an American surgeon, Conrad Miller, who began in the late 19th century, and described in 1926 his implant material as ‘quite a variety of foreign materials … bits of braided silk, bits of silk floss, particles of celluloid, gutta-percha, vegetable ivory, and several other insoluble foreign materials.’1

The materials were used in a net structure or criss-crossing technique. This stimulates a foreign body (FB) reaction to promote collagen formation to create a denser dermal and subdermal plane. However, this FB reaction results mainly in type III collagen, protective but fibrotic scar-like tissue.

The first surgical face lifting procedures began in the 1920s, but the anaesthesia techniques were not particularly safe, and these operations were heavily criticised2.

Suspension techniques

Suspension techniques were revived in the late 1990s with the use of gold threads that had already been in use since the 1950s; then again more recently with the ‘Korean’ or ‘PDO’ threads, in an attempt to have less invasive techniques to try and tighten facial skin. But they are ‘passive’ techniques acting through fibrosis.

The loops were also advocated more recently in association with surgical face lifting, in order to minimise the drawbacks of the procedure. This was achieved either through the suspension of the malar fat pad during a face-lift procedure by 4-0 nylon mattress sutures suspended to the superficial temporal fascia3 or as two or three loops positioned to lift and maintain the posterior, middle, and anterior zones of the cheek4.

Unfortunately, the results appeared to many surgeons to have less durability than expected, as demonstrated by Kestemont5 confirming the ‘cheese wire’ effect of simple suture threads within the soft tissue of the face.

Nicanor Isse, from the USA, started to use ‘cogs’ or ‘hooks’ slit in a polypropylene suture in 1996, but these were later known under the name of ‘Aptos’ from 1999 and mentioned in a study published in 20026. Ìt was the first real attempt to assert a true self-suspending effect to the soft tissues of the face, as the anchoring occurs over the entire length of the thread.

Like many new innovative ideas, it became very popular and widely used. Many other brands are now available, uni or bidirectional, looped, resorbable or permanent. However, clinically some results proved to be somewhat disappointing, with asymmetries, short lasting results, and thread breakage. Hellig et al.7 stated that ‘Barbed sutures clinically seem to provide little traction on tissue after one month of healing.’

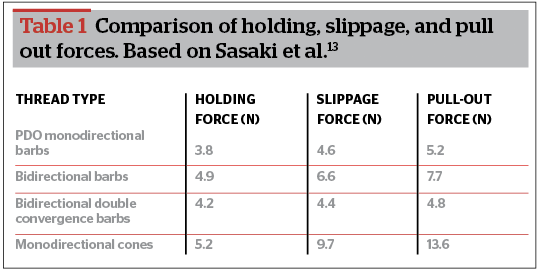

In a study on cadaver faces, Sasaki et al.8 demonstrated that holding tension, slippage tension, and pull-out tension were significantly lower with straight barbed sutures in comparison to looped ones9 (Table 1 comparison of holding, slippage, and pull out forces).

In a study published in 2010, Rachel et al.10 challenged the goal of the barb suture lift, which was thought to be ‘to deliver predictable long-term results while providing less morbidity, less downtime, greater patient satisfaction.’ In the study, they stated that ‘the results of this study indicate that the barbed suture lift was unable to accomplish these goals.’

Cone sutures

The surface of the anchoring proved stable and efficient, to the extent that the threads could be retightened after 2 or 3 years12. These holding capacities were well demonstrated by Sasaki in 200813, and Silhouette Lift threads were used for tightening other areas of the body, such as the gluteus14. But they needed to be inserted through an opening in the temporal region in the face and attached to the temporalis fascia.

In 2011, the Silhouette Soft threads were commercialised. They consist of resorbable poly-L-lactic acid for the thread and L-lactic acid (82%) and glycolic copolymer (18%) for the cones, with a bidirectional orientation to the cones. They exist in either four cones on either side separated by knots 5 mm apart, or with 6 or 8 cones separated by knots 8 mm apart on either side.

There is less weight applied to each cone; thus less tension, and no need for a skin opening, which, although minimally invasive, proved to be an issue for many patients.

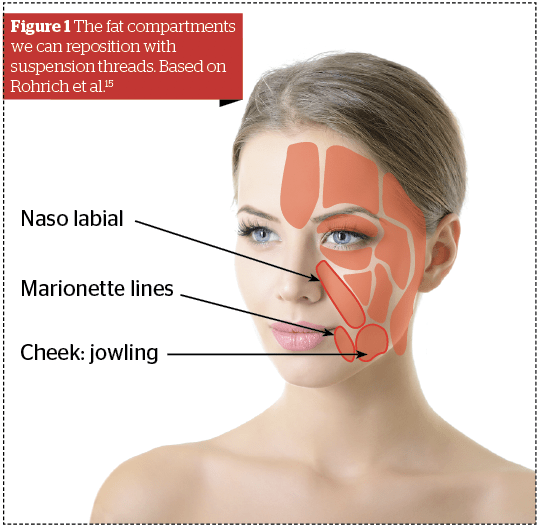

The main difference between the cone and the cog technology is not so much the appearance than their holding capacity. Following the description of the fat compartments by Rorich et al15, and with a better understanding of the changes that occur in the face with ageing16,17, we now know that skin follows the displacement of the deep tissues, and that nasolabial folds, marionette lines, and jowls are associated with fat compartment modifications and muscular retraction18, 19.

Therefore, the treatment to this tissue displacement should not be filling the folds, but repositioning these compartments, (Figure 1: The fat compartments we can reposition with suspension threads) and this should be the aim of tensioning threads, instead of trying to pull the skin backwards and/or upwards. To attain this objective, a strong anchoring in the soft sub-dermal fat is mandatory.

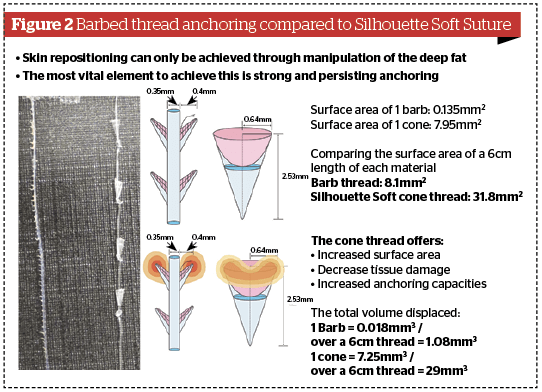

Following a study by G. Sasaki8, K. Hong20, a dermatologist in Seoul, compared the surface of contact of the cogs and the cones. He found that the surface area of 1 barb was 0.135 mm2 whereas the surface area of the aperture of 1 cone is 7.95 mm2, which is nearly 60 times greater. Considering the number over a 6 cm length of cogs (60) and cones (4), the total surface of contact is 8.1 mm2 for the cogs and 38.1 mm2 for the cones, which is almost four times more (Figure 2).

But more than the surface of contact, it is the volume displaced, which seems to be the main factor to anchoring. The cones of Silhouette Soft are not completely conical but represent a fulcrum, i.e. a truncated cone. The volume displaced by a barb is 0.018 mm3, and is 7.25 mm3 for a cone, the total over 6 cm being a little over 1 mm3 for 60 barbs and 29 times more for 4 cones (29 mm3). For a 16 cone thread over a length of 24 cm, the total volume is 116 mm3, and, for the corresponding 240 cogs, it is 4.32 mm3.

Another factor seldom taken into account is the physical properties of the different materials used. In a French publication, Guillo22 compared the total retention time, i.e. the time the thread would hold the original tension applied, and the total mass loss time, i.e. the time it takes for the suture to dissolve completely.

The results showed that polydioxanone will maintain the original tension for approximately 3 to 4 weeks, and will be absorbed in less than 6 months. On the contrary, PLLA sutures will possess a duration of 3 months for the tension, and 18 months before disappearing, leaving enough time for a sufficient collagen type I stimulation as demonstrated by P.R.Russo and F. Vercesi23.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the cone technology of the resorbable Silhouette Soft sutures provides a greater and stronger anchoring of the threads with less material than the barbs, being more efficient for repositioning the displaced structures of the aged face, and increasing the collagen type I content of the skin. Multiplying the number of threads to try and improve the overall holding strength of the barbs means much greater risks of side-effects or complications due either to local trauma, such as bleeding or oedema; risks associated with the insertion technique, like skin irregularities and pain; or due to the holding capacities themselves, such as displacement, extrusion or asymmetries, as stated by Lycka24 and later by Rachel et al10.

Declaration of interest Dr Nicolau is a medical advisor and trainer for Sinclair Pharma

Figures 1 © Rohrich RJ, image © Adobe Stock;

Figure 2 © Nicolau P

Table 1 © Sasaki GH