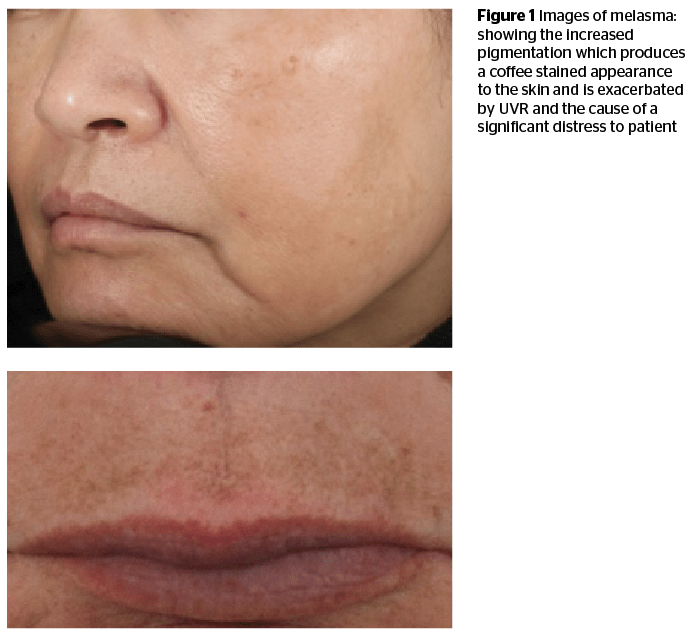

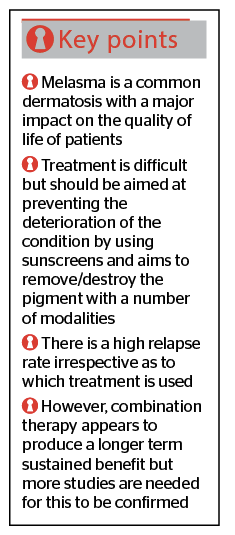

Dr Sandeep Cliff and Nikita Cliff-Patel consider the triggers, diagnosis and current treatment options for melasma based on a review of the available literature

Melasma is a chronic acquired condition that results in hyperpigmentation of the skin1. It predominantly affects the sun-exposed sites of the face; however, other areas such as the forearms have been reported as well as other non-facial sites2. Melasma has a significant effect on the quality of life of its sufferers, and although it is a common dermatosis, an effective, sustainable and reproducible treatment still eludes us. Understandably, this is both frustrating for practitioners and their patients alike. Nevertheless, there have been some breakthroughs in the treatment of melasma; this article will discuss current treatment options and also present clinical studies undertaken to date highlighting the numerous treatments and their varying success.

Assessment and diagnosis

Melasma is classified according to where the pigment is located within the skin, more specifically the epidermal layer, dermal layer or a combination of the two. As expected, dermal melasma carries the worst prognosis due to the difficulty in treatment modalities ‘attacking’ this pigment located deep in the dermis. The identification of the specific type of melasma can be made with the use of Wood’s light4. This device emits UVA light and is a useful tool in identifying the location of the pigment. Epidermal pigment is enhanced under Wood’s light while dermal pigmentation remains unchanged; furthermore, ‘mixed’ pigmentation, the most common form of melasma, produces a spotty appearance as it reflects the fluctuating location of the pigment. Unfortunately, the Wood’s light examination is difficult to interpret in darker skin patients in whom melasma is more common.

Histological examination of skin biopsies in patients with melasma have been undertaken for research studies and highlight a number of interesting findings4. These include solar elastosis, otherwise described as an accumulation of elastic fibres that are fragmented in the dermis of the skin, this may either reflect the location of the condition or may be central to the aetiology of the condition. There is also basement membrane disruption that facilitates pigment deposition into the dermis and increased dermal vascular activity, suggesting that potentially an antiangiogenic treatment modality may be of some benefit — hence the use of vascular lasers in some studies with varying success. However, whether these changes are initiating features or secondary still remains unknown.

Triggers

It would appear that the major triggering factor and subsequent aggravating factor for this condition is ultraviolet light, which stimulates an increase in both melanocytic hyperplasia and melanosome production. There is some controversy as to whether topical cosmetics and fragrances can induce melasma, some studies suggest these products can trigger photocontact dermatitis9, which is a known precursor for melasma. From the authors’ experience, they have found that for the majority of melasma sufferers there is neither a conforming history nor is the distribution of the pigmentation suggestive of the role of photocontact dermatitis as a precursor.

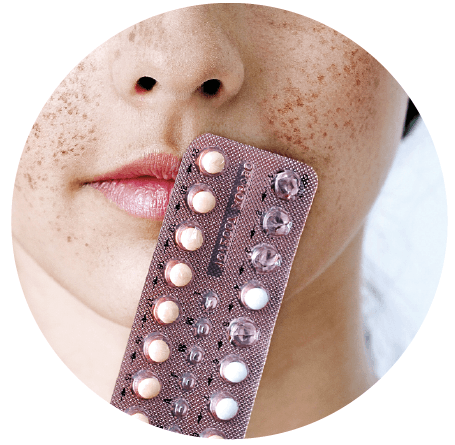

The most prominent factor involved in the formation of melasma is sex hormones, more specifically during pregnancy or via the oral contraceptive pill (OCP) and hormone replacement therapy. One study presented a group of women on the OCP in 196710–12 who all developed melasma, 87% of these women then went on to develop the condition during subsequent pregnancies. This suggests an event that triggers melasma, namely the OCP, which may then have predisposed these women to subsequent flare-ups, a feature that is frequently seen in practice. A further study looked at the sex hormones in specific patients and noted a persistently elevated 17‑beta-oestrodiol in the melasma group, this suggests these circulating oestrogens may constitute a risk factor and a potential maintainer of the disease13. It would appear that oestrogen plays a role in stimulating the expression of melanocortin type-1 receptors in vitro and are involved in the pathophysiology of melasma.

Melasma is not infrequently seen in pregnancy, consequently, there is a well-recognised elevation of melanocyte stimulating hormone in pregnancy, leading to an increased transcription of tyrosinase. Tyrosinase is an oxidase that appears to be the rate-limiting enzyme for controlling the production of melanin. Therefore, the association with oestrogen and melasma has a scientific basis but why particular patients suffer from this condition and others do not remains unknown.

In 200316, a validated quality of life questionnaire was developed, specifically addressing the impact melasma has on the emotional state, social relationships and daily activities of the sufferer. This disease-specific questionnaire has greater discriminatory power when compared to the other general questionnaires. A Brazilian study reported that 65% of respondents reported discomfort from the condition, 55% felt frustration and 57% were embarrassed about this aspect of their skin17. It is not unexpected to witness these results in response to a condition that is visible, difficult to conceal and somewhat resistant to treat and long lasting, nonetheless, these studies serve to highlight, reinforce and also to encourage treatment developments for this condition.

Treatment

Treatment of this condition focuses on the pigmentation and its removal by a number of modalities. Clearly for a condition with such a severe impact on patients, prevention would be far better than cure, however, in the absence of clear, reproducible causes, practitioners often have no choice but to resort to the treatment of the pigment assuming all other differentials have been excluded. The authors acknowledge that those with principally epidermal melasma are more likely to respond to treatments, than dermal and mixed melasma, respectively. Therefore, pigment reduction is tackled by the slowing down of melanocyte proliferation, the inhibition of melanosome formation and synthesis and, finally, the enhancement of melanosome degradation. Broadly speaking, treatment is subdivided into first line therapy using photoprotection18, camouflage and topical compounds that affect melanin synthesis. The second line treatment involves the use of chemical peels and third line treatment uses light and laser therapies. The treatments are ranked based on ease of use and additionally on the effectiveness of the treatment along with the potential side-effects19–22.

Sun protection

It is recommended to use large quantities of broad spectrum sunscreen with increased frequency as there is significant evidence to suggest using either chemical or physical blocks are incredibly effective and their value should not be underestimated18. Furthermore, numerous studies have shown the positive response of melasma to adequate photoprotection and the protection against relapses with sufficient use19.

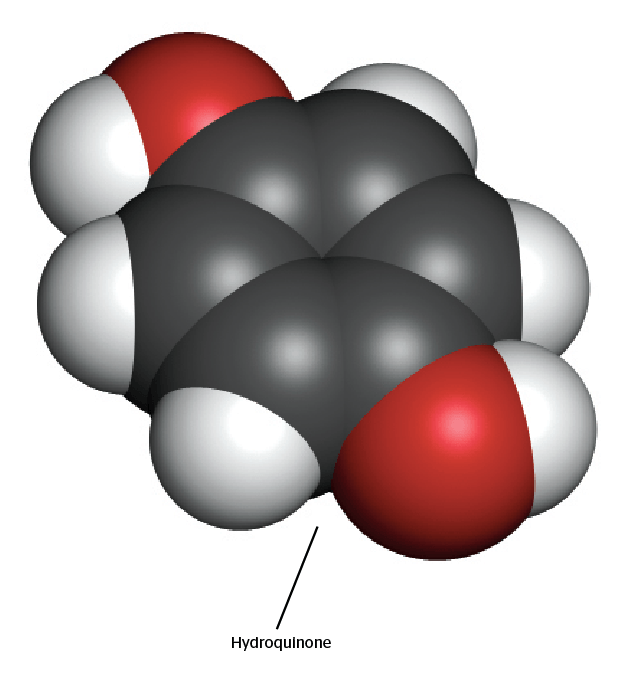

Hydroquinone

Hydroquinone blocks one of the conversion steps of tyrosinase that ultimately inhibits the formation of melanin while simultaneously enhancing membranous damage to the melanocyte leading to necrosis of the whole melanocyte. Percentages of between 2-4% are frequently used, on occasion higher concentrations are also used. Higher concentrations are less commonly used due to the risk of ochronosis and irritation, while their availability restricted in many countries. It is important to note that irritation from hydroquinone treatment can be mitigated against by combination therapy as discussed later on. The positive effects of hydroquinone become apparent after 6 weeks and treatment should be continued for up to 12 months. The lead author has witnessed hydroquinone related ochronosis in a patient who obtained 20% hydroquinone on the Internet and had been using it for over 12 months. It, unfortunately, proved to be persistent, difficult to treat and devastating for the patient; however, they have not personally seen ochronosis in any patient using lower concentrations for short periods of time.

Kojic acid

Kojic acid is an effective depigmenting product that inhibits tyrosinase by chelating copper, it is used in concentrations up to 4% but is a sensitizer, so caution must be exerted23. It is present in a number of topical preparations and there have been varying reports of its clinical effectiveness.

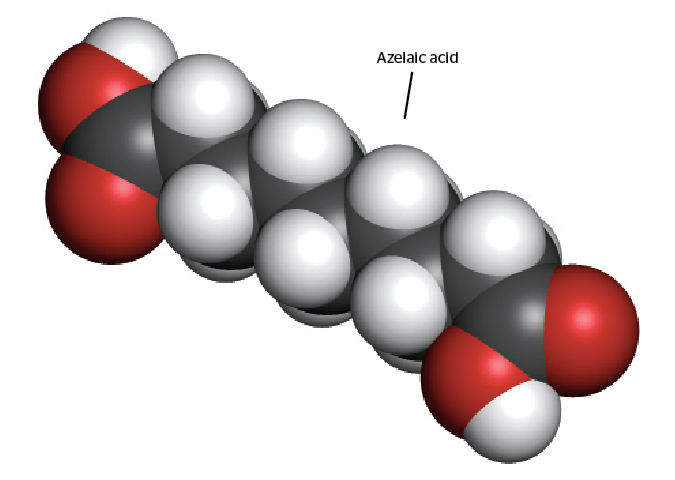

Azelaic acid

Many practitioners who may have limited access to hydroquinone products may use azelaic acid, which inhibits tyrosinase activity. Azelaic acid is well tolerated and can be as effective as hydroquinone although this is refuted by some clinical trials19.

Triple combination therapy

The most frequent topical therapy used is the triple combination and this was created to enhance the effectiveness of individual products, shorten the treatment length and limit the potential for adverse effects23, 24. Triple combination therapy is composed of hydroquinone, retinoic acid and a topical steroid. For example, tretinoin limits the oxidation of hydroquinone and improves epidermal penetration while the steroid reduces irritation and, as a result, triple therapy leads to a faster response with fewer side-effects.

The topical steroid used is frequently of a low potency, this is because higher potency steroids have been shown to have both a higher side-effect profile and a higher relapse rate so should be prescribed with caution. A number of studies have now been undertaken to look at the efficacy of this treatment, side-effect profile and patient tolerability with good outcomes. There have been further studies looking at potential atrophy using histological assessment which conveys an extremely low risk even after 6 months of continued use24.

Dual therapy preparations are also available for patients in countries where either triple therapy is not available or patients may be intolerant to one component of the treatment; these combinations contain both hydroquinone and kojic acid.

Chemical peels

If the above does not work, only partially works or there is a relapse following initial response then the next option would include chemical peels either in isolation or in combination20. Chemical peeling is the application of a chemical agent to the skin, which leads to the controlled destruction of the epidermis with or without the dermis. This leads to skin exfoliation and the removal of tissue followed by regeneration of both the epidermal and dermal tissues. This mode of action can be applied to the treatment melasma and causes the removal of melanin via the controlled chemical burn to the skin. As expected, this treatment appears to be most effective for epidermal melasma. There are some limitations to their use in dark-skinned patients (Fitzpatrick skin type IV plus) due to the prolonged dyspigmentation, which can in some cases be permanent. The most commonly used peel is the glycolic acid peel, this is an alpha-hydroxy peel used in concentrations of 30–70% that is repeated every 4 weeks. It is usually left on the skin for 3 minutes and then neutralised. Studies looking at peels used in isolation or in combination with triple therapy show the combined approach seems to be more effective than the triple therapy used in isolation, however, some of the relevant studies are conflicting25.

Salicylic acid

Citric acid

Citric acid26, an alpha hydroxy fruit acid, significantly reduces melanin expression in melanocytes in in vitro skin equivalent models relative to the water control. This feature of citric acid has been exploited to the advantage of melasma sufferers with the use of citric acid peels (30%), which have produced a reduction in pigment production.

Jessner peel

The Jessner peel consists of resorcinol, salicylic acid and lactic acid in ethanol and has been shown to be an effective peel for epidermal melasma20,27. A combination of Jessner peel with a trichloroacetic peel (35%) allows for a more uniform penetration to a deeper depth. This could potentially be an option for dermal melasma, however, it is too early to comment. The concern with a deeper peel is the problem of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and the risk of scarring22.

An interesting modification of the peels concept is the phytic peel, which is essentially an alpha-hydroxy peel that does not require neutralisation, thus reducing the risk of the potential complication of a ‘burn’. The phytic peel has a low pH and is left on overnight, therefore negating the risk of over peeling. There is considerable interest in this type of peel and they may be the way forward for chemical peels, as they appear to have a better safety profile.

Laser therapy

Lasers have been tried extensively in the treatment of melasma with varying success, the premise being that the target is the melanin and the depth of the pigment is variable hence the need to consider a variety of laser options, which will be absorbed by melanin but simultaneously penetrate to different depths. More recently, the field of laser surgery has been revolutionised by the introduction of fractional photothermolysis, this involves the light producing columns of thermal injury but sparing the surrounding untreated skin, consequently, this produces less downtime and fewer side-effects28. This new concept of fractional photothermolysis is showing promise with deeper penetration, no skin ablation and greater targeted inflammation: all of which serve to offer targeted treatment. Comparison of triple therapy with fractional laser shows greater patient satisfaction with the latter but repigmentation was noted with the laser in all cases28.

Q-switched laser

One of the first lasers to be used in relation to the treatment of melasma was the Q-switched Nd:YAG, which targeted melanin while also producing some damage to the vascular plexus, this also appears to be one of the possible factors associated with the pathogenesis of the condition. There are many studies showing the effectiveness of this laser, however, they all show that patients develop a recurrence of their melasma once treatment is discontinued. The relapse rate can be reduced by so called ‘laser tonin

Interestingly, as the authors’ introduction alluded too, increased vascularity is associated with melasma, although the cause or effect remains unknown. There is evidence to suggest using a vascular selective laser may have some benefit in melasma, and, specifically, one study showed some benefit in skin type I–III28.

Intense pulsed light

Intense pulsed light (IPL) was developed in the 1990s30, it involves using a lamp that emits light that is neither coherent nor collimated and has a wide spectrum (500–1200 nm). The mode of action involves the absorption of light by melanin both in melanocytes and keratinocytes that leads to epidermal coagulation followed by crust formation, which when shed removes the pigment leading to a clinical improvement. Once again, superior results were noted in cases with epidermal melasma, there were improvements of up to 100% noted although some patients did develop post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. Another study comparing IPL and hydroquinone versus hydroquinone alone showed superiority with the combination therapy but relapse within 6 months was common and the study advocated the need for ongoing treatment30.

As with a lot of lasers and chemical treatments the greatest risk of intense pulsed light treatment remains post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, this can prove to be stubborn, persistent and difficult to treat. As a result, the need to ensure copious amounts of sunblock is used is paramount and, as delineated previously, the preparation of the skin prior to treatment with therapies to minimise pigmentation is also of great importance.

Conclusion

This review article on melasma has attempted to look at the aetiology and pathophysiology of this common dermatosis, it has also touched on numerous studies that confirm the deleterious effect melasma has on patients, which can also severely affect their quality of life. An algorithm19,31 of treatment has been presented to allow the practitioner to introduce treatments in a logical way in order to maximise response yet minimise adverse effects.

However, it would appear that without exception there is a large relapse rate for this condition irrespective of the treatments being offered.

It remains incumbent upon clinicians to be candid with their patients to manage their expectations, to ensure that patients understand the disease and to be realistic. The authors do however feel that having read the numerous articles on this condition, one can be sanguine about the future of the management of melasma — with the recognition of this condition being common and having a deleterious effect on the patient’s quality of life — there is active research ongoing looking at more effective ways to treat this condition to produce a sustained clinical response.