Dr. Didac Barco discusses using a combinational approach on a 31-year-old female patient suffering from acne scars

Acne vulgaris represents a very widespread condition. In Spain, according to the AEDV (Spanish Academy for Dermatology and Venerology), up to 80% of young people aged between 12–18 suffer from this condition. Among those in their 30s, 3% of males and 11–12% of women, also have acne vulgaris. This is an inflammatory process localised to the pilosebaceous units, mainly in the face, chest, upper arms, and back(1). Acne affects the face in most of the cases, with many patients experiencing some degree of scarring, the severity of which correlates to the acne grade(2). Acne scars are the result of an altered wound healing response to cutaneous inflammation, with inflammatory cell infiltrates found in 77% of atrophic scars3. We can find different scar types typically on the same person: Ice pick scars comprise 60 to 70% of atrophic scars. These narrow, less-than-2 mm, ‘v’- shaped epithelial tracts have a sharp margin that extends vertically to the deep dermis or subcutaneous tissue. Depth of involvement makes ice pick scars resistant to conventional skin resurfacing options. Boxcar scars comprise 20 to 30% of atrophic scars. These scars are wider, 1.5-4.0 mm, round-to-oval depressions with sharply demarcated vertical edges. Shallow boxcar scars (0.1–0.5 mm) are amenable to skin resurfacing treatments, whereas deep boxcar scars (≥0.5 mm) are resistant. Finally, rolling scars comprise 15 to 25% of atrophic scars. These scars are the widest and may reach up to 5 mm in diameter.

“Ablative lasers offer a significant improvement in scar appearance with collagen contraction, remodelling, and skin tightening. “

Treatment of generalised atrophic acne scars involves several techniques as well as other medical approaches. Among these techniques and treatments, we can find lasers, drugs, chemical peels, dermabrasion, micro-needling and radiofrequency.

Mechanism of action

The options for laser treatment for acne scarring have expanded in recent years and have gained in popularity given their results. Lasers for acne scarring fall under two main categories: ablative (classic or traditional, and fractional) and non-ablative (traditional and fractional)(4).

Classic ablative lasers are considered the gold standard in acne scarring treatment. Ablative lasers offer a significant improvement in scar appearance with collagen contraction, remodelling, and skin tightening. Improvement is significant after one treatment session, compared to multiple sessions required with non-ablative lasers. Among classic ablative lasers used for acne scarring, the 10,600 nm CO2 laser is reported to deliver the most efficient results. The chromophore for this wavelength is water. From an 18-month prospective, uncontrolled study of 60 patients with moderate-to-severe atrophic facial acne scars, it was demonstrated significant immediate and prolonged improvement in skin tone, texture, and appearance after one treatment session of a CO2 laser. Clinical improvement scores were 69% at one month and 75% at 18 months. In addition, persistent collagen formation was defined on histologic samples 18 months post-procedure(5).

In reference to fractional ablative CO2 lasers, in a study of 13 patients (skin phototypes I–IV) with moderate-to-severe acne scars, treated with fractional CO2 laser showed significant improvements of 26 to 50 percent on a quartile scale and improved scar depths of 66.6%(6). All patients experienced erythema, which resolved within one month in most patients.

The CO2RE system (Candela, USA) is a CO2 laser (wavelength of 10600 nm) that can be used in classic or fractional mode, providing the physician with the ability to choose or combine both modes for a better approach to acne scar treatment. This system provides a unique way of delivering the fractionated energy. Using the deep fractional mode, it can reach a depth of penetration of up to 800 micrometres, with a low-density pattern in order to avoid excessive thermal injury (high energy, low density). A novel technique combining classic and fractional modes is discussed in this case report.

Case study

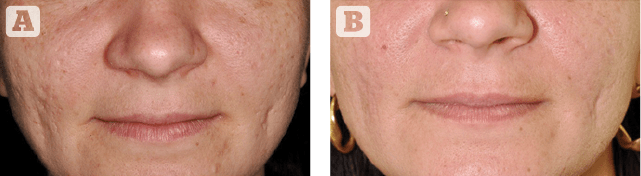

We present the case of a 31 year old woman suffering for 10 years with boxcar, ice pick and rolling acne scars on both of her cheeks (Figure 1). She did not have any noteworthy medical conditions and never had previous treatment for her scarring. She agreed to undergo two sessions of CO2 laser, half a year apart. Both sessions consisted of a limited CO2 classic resurfacing at the centre and borders of the scars in a pinpoint technique-like fashion(7) and fractional CO2 resurfacing in both cheeks, combined in the same treatment.

Materials and methods

A 7% prilocaine and 7% lidocaine mix cream was applied thirty minutes before the procedure. A picture was taken using a Nikon D90 camera prior to the treatment. The scars were treated with the CO2RE CO2 fractional laser system (CO2RE, Candela, USA). We applied a single pulse of classic-resurfacing mode 3 mJ at the centre and borders of the scars. We then used the deep fractional mode at 70 mJ on top of the scars and in the surrounding skin. Fusidic acid 2.5% ointment was applied to the scabbing every 12 hours for 7 days. The patient also applied Epitheliale AH duo cream (A-derma laboratories, Bruges) every 6 hours for 10 days. After 6 months and noticeable improvement, the patient underwent a second session of the same procedure. A picture was taken using the same system three months after the second treatment session (Figure 2). No secondary effects or complications were recorded.

Objective

This technique takes advantage of the efficacy of the classic CO2 full resurfacing in the most severe scars but using it in limited areas in order to reduce the secondary effects that may be associated with this technique (persistent erythema, hyper or hypopigmentation and scarring)(8). To boost collagen production and to improve the general texture of the skin where the scars were set, we performed a fractional CO2 resurfacing in deep mode, to take advantage of the safety profile of this technique applied in a wider area compared to that of the classic resurfacing. Limiting aggressive techniques to the most affected areas for acne scarring and using safer alternatives in a wider fashion has been described previously(9). Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to use a CO2 laser in both full-resurfacing mode and fractional mode in the same treatment to make the most of their mode-specific advantages.

A 7% prilocaine and 7% lidocaine mix cream was applied thirty minutes before the procedure.

Conclusions

Total depth-controlled limited destruction of the epidermis and dermis with CO2 classic resurfacing offers the best clinical results to improve atrophic acne scars but patients have a longer downtime period and it may also be associated to long-term complications such as pigmentary disorders, erythema and scarring(10). The use of fractional CO2 laser lowers this risk as well as the efficiency of every treatment. Hence, we may take the benefits of both treatment settings and decrease their risks by combining these two techniques in the same session. Limiting the classic CO2 resurfacing at the most severely affected areas to maintain a high efficacy profile, and treating a generous area with the fractional CO2 laser to stimulate collagen production reducing appears to be a safe and effective combination treatment to address atrophic acne scarring.

Declaration of interest Funding for submission of this paper was provided by Candela

Figures 1-2 © Didac Barco

References

- Kang s, Cho s, Chung JH, et al. Inflammation and extracellular matrix degradation mediated by activated transcription factors nuclear factor kappaB and activator protein-1 in inflammatory acne lesions in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1691–1699.

- Layton AM, Henderson CA, Cunliffe WJ. A clinical evaluation of acne scarring and its incidence. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:303–308.

- Lee WJ, Jung HJ, Lim HJ, et al. Serial sections of atrophic acne scars help in the interpretation of microscopic findings and the selection of good therapeutic modalities. J Eur Acad Dermatol. venereol 2013;27:643–646.

- Connolly V, Saedi N, et al. Acne scarring- Pathogenesis, Evaluation and Treatment Options. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10(9):12–23

- Rivera AE. Acne scarring: a review and current treatment modalities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:659–676.

- Chapas AM, Brightman L, Sukal S, et al. Successful treatment of acneiform scarring with co2 ablative fractional resurfacing. Lasers Surg. Med 2008;40:381–386.

- Kim S. Clinical trial of a pinpoint irradiation technique with the CO2 laser for the treatment of atrophic acne scars. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2008 Sep;10(3):177-80

- Read-Fuller AM, Yates DM, Vu DD, Hoopman JE, Finn RA. Problems and complications of full-face carbon dioxide laser resurfacing for pathological lesions of the skin. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2017 Jan;123(1):e10-e15.

- Schweiger ES, Sundick L. Focal Acne Scar Treatment (FAST), a new approach to atrophic acne scars: a case series. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013 Oct;12(10):1163-7.

- You HJ, Kim DW, Yoon ES, Park SH. Comparison of four different lasers for acne scars: Resurfacing and fractional lasers. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016 Apr;69(4):e87-95