Leonardo Marini, MD, PhD, discusses two recent cases of treating melasma in female patients with a new 5% cysteamine topical formulation

Afortunate woman craves nothing but a good anti‑depressant cream, said a patient with long-lasting, unpleasant to be seen, skin hyperpigmentation, desperate to find an effective and durable solution to the frustrating skin disorder she faced reflected in the mirror every single day of her life.

Melasma is a well-known reactive skin hyperpigmentation disorder that is difficult to treat and control. In some cases, it can even variably affect mental health, social life, and emotional well being of less fortunate patients. Melasma typically presents with irregular patches, dark yellow to variable hues of brown in colour, mostly distributed on sun-exposed facial skin regions1-3. Retrospectively, various natural and synthetic formulations have been proposed to treat unpleasant skin hyperpigmentations. Centuries ago, topical formulations containing ammonia salts of mercury and potassium hydroxide were used but their highly toxic biological behaviour, once discovered, made them less popular4,5. In the recent past, intensive research was devoted to finding a safe and reliable solution to treat unwanted skin hyper-pigmentations effectively and durably. Since the 1960s, hydroquinone has been considered as the gold standard topical anti-melasma agent in the United States6. After some time, several studies revealed that hydroquinone-containing formulations, in spite of their significant degree of success, have a low safety profile. The increased risk of renal carcinoma noted in rodent models taking oral hydroquinone as well as exogenous ochronosis induced by prolonged use of topical formulations containing this agent led to the release of a warning report from the World Health Organization in 1997. After that, hydroquinone was banned and/or its use strictly regulated in several countries around the World7.

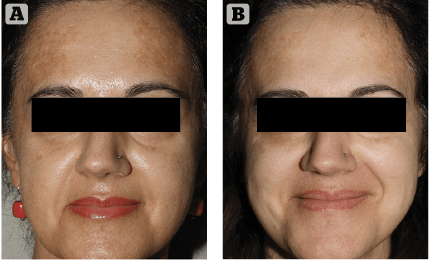

Figure 1 (A) Prior to treatment and (B) After 4 weeks of treatment

In 1975, Albert Kligman introduced his triple-active-ingredient topical formula (KF). It contained hydroquinone, retinoic acid, and dexamethasone synergistically acting together to produce an effective skin bleaching effect. After it was made available on the market, it proved to be the most effective topical solution to treat melasma8,9. Despite its high degree of efficacy, variable levels of side-effects were observed, such as skin hypotrophy related to prolonged contact with topical corticosteroids contained in the formulation, ochronosis, irritative skin alterations. These side-effects were observed more intensively as topical treatment progressed in time thus preventing long-term use of KF as maintenance therapy10,11.

While hydroquinone was having its golden time as a successful skin bleaching agent, research focusing on alternative, effective solutions still progressed, and in 1966, Chavin et al. introduced cysteamine. As a naturally synthesised anti-oxidant agent derived from L-cysteine, cysteamine showed excellent pigment suppressing properties when injected subcutaneously in black goldfish. Further studies were made and, in 2000, Qui et al. confirmed that cysteamine was to able to reduce melanin synthesis by 80% in cultured B16 melanocytes12,13. Other independent studies also confirmed cysteamine’s stronger depigmentation effect when compared with hydroquinone14,15. In spite of its excellent pigment-suppressing properties, cysteamine had a major problem; its rapid oxidation was associated with the liberation of an extremely unpleasant odour preventing its use in any topical preparations. The solution to this seemingly unsolvable problem came, as it is often the case, after an accidental ‘error’ during a laboratory experiment. Behrooz Kasraee, an Iranian born dermatologist researcher, discovered how to effectively neutralise cysteamine’s foul odour while preserving its pigment suppressing properties.

In recent years, these important innovations led to the introduction of cysteamine in the highly competitive world of skin depigmenting agents and a 5% topical formulation was made available on the market.

Figure 2 (A) Prior to treatment and (B) After 4 weeks of treatment

As it always happens when the medical devices market proposes new skin hyperpigmentation suppressants, cautious optimism and investigative scepticism are the rule. We introduced this innovative topical formulation to two extremely cooperative patients affected by melasma. They were extremely frustrated by their unresponsive, long-lasting skin depigmenting disorder. After discussing the rationale of this innovative topical treatment, along with its potential benefits and side effects, written informed consent was obtained. The first case was a 34-year-old female patient suffering from progressively worsening melasma for 2 years prior. Her irregularly shaped hyperpigmented brownish patches were most evident on her fronto-glabellar region, upper-lip and cheeks. Minimal spontaneous improvement was noted during winter months consistently followed by intense worsening associated with UV exposure during spring and summer, in spite of ‘religious’ use of high SPF (50+) balanced sunscreens. Melasma onset was reported after one year of oral contraceptive medication. The patient reported two 6-month cycles of modified topical KF with a minimal depigmenting effect on her brown patches in spite of evident, disturbing skin irritation. The second case was a 54-year-old female patient who reported to be affected by melasma for 6 years. Her hyperpigmented patches were mostly distributed on the lateral thirds of her frontal region. As usually seen in this kind of reactive hyperpigmentation disorder, the clinical situation was reported to worsen after intense UV exposure. She tried three 6 month cycles of topical modified KF, which revealed progressively less effective skin pigmentation control with time. Both patients had a positive history of insufficiently protected, intense UV exposure during their younger years, followed by relatively recent, properly balanced high SPF sunscreens. Neither patient reported irregularities associated with their menstrual cycles during the last 5 years.

Treatment plan

We always like to prepare the skin to improve and optimise trans-epidermal penetration of topical actives. Our protocol consists of four full face low-pressure microdermabrasion sessions (MegaPeel — Dermamed Solutions, USA), scheduled every 15 days. In addition, a twenty-minute contact 5% hydroquinone peel-off mask (LEM— Laboratorio Ecoceutico Magistrale, Italy) was applied immediately after the first and last microdermabrasion sessions.

As a second step, patients were instructed to apply Cyspera (Scientis, Switzerland) — intensive 5% cysteamine pigment corrector cream — 15-min skin contact time, at bedtime for 4 weeks followed by one application always at bedtime, two non-consecutive nights per week as maintenance therapy according to the producer suggested protocol. Morning topical skin treatment routine consisted of 15% azelaic acid gel (Finacea, Bayer, Germany) to be applied immediately after gentle facial moisturization with spring thermal water (La Roche Posay Laboratoires, France). This step was immediately followed by topical application of Hyalu B5 hyaluronic acid serum (La Roche Posay Laboratoires, France) and a soothing/hydrating cream (Cream for Intolerant Skin – Avene Laboratoires, France). Topical sun protection (Fotoprotector 100+ Spot-prevent ISDN-Spain) was prescribed daily during the course of treatment.

Results

Clinical exam and standard clinical photography (Canon digital camera with a 50 mm macro lens and dedicated TTL flashlight) revealed a drastic, almost uniform depigmentation of melasma in the first case and a significant intensity decrease of localised hyperpigmentation in the second patient. No side-effects or complications were reported or observed during the course of the treatment. Patients’ clinical perception of Cyspera Intensive Pigment Corrector Cream treatment was reported good and effective (Figure 1). They both expressed a strong sense of positive confidence in the topical treatment prescribed.

Our case report, even if considering two patients only, showed that Cyspera (5% cysteamine cream) was an extremely effective, well accepted, complication-free depigmenting formulation particularly considering that both cases have been previously treated with multiple modified KF cycles. We can happily confirm that we are entirely in line with the results produced by other much more extensive studies recently published16–18.

If we consider that cysteamine is a non-cytotoxic, non-mutagenic, and non-carcinogenic depigmenting active compared with hydroquinone containing formulations, there is little doubt about what to choose when planning melasma treatment. Very possibly the long-awaited anti-depressant skin bleaching cream might have been found after all.

Declaration of interest None

Figures 1 & 2 © Dr Marini