The article describes how to fill the tear trough with hyaluronic acid, and proposes an original five-point scale with regard to its depth and the age of the patient. It is evident that any aesthetic treatment requires a perfect understanding of anatomy, physiology and the ageing process. This article suggests the appropriate treatment, explains the technology, its safety, and potential adverse events. Patient assessment requires consideration of the best cosmetic investment for the patient.

The palpebromalar groove forms the transitional zone between the lower eyelid and the upper part of the mid-face. This article is only concerned with addressing the volume of the under‑eye groove, and the shadows caused by the hollowing of the area, but not the pigmented dark circles.

In general, hollowing of this area is less apparent in the young (Figure 1), although certain young people can have circles caused by hypoplasia of the fatty tissue in this area. Usually, the hollowing of the palpebromalar groove is evident in the ageing process, during which the tissue sags and there is an age-related fat atrophy (Figure 2). With age, the groove under the lower eyelid can become deeper, and the lower eyelid elongated. The tear trough is one of the prominent signs of ageing owing to a loss of volume in this region, coupled with the descent of the superficial malar fat pad1, 2.

Plastic and aesthetic surgeons, aesthetic dermatologists, and aesthetic physicians aim to embellish and/or rejuvenate the faces of their patients, harmonising the volumes and so erasing any hollows and shadows.

A perfect understanding of the anatomy of the face, its physiology, and dynamic and age-induced reshaping is paramount. Mastering the techniques and products used to achieve the aesthetic goal is essential.

Understanding the anatomy and physiology

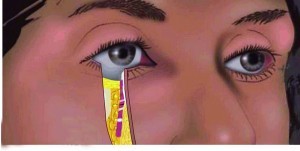

With regard to facial anatomy, the area of interest for this article is the upper portion of the mid-face until the rim of the orbit (Figure 3). Structurally, it shares elements with the mid-face, as described below3, 4. The rim of the inferior of the orbit forms the skeletal bony base. The deep malar fat (suborbicularis oculi fat; SOOF) is a fine strip at this level, attached at the rim of the orbit. Dense and somewhat fibrous, it forms the shield of protection for the inferior orbital rim just as the Charpy’s fat pad protects the superior orbital rim. As a result of its deep bony adherence, this fat is fixed. Immobile in the facial dynamic of facial expressions, this deep fat does not sag with the tissue relaxation caused during ageing. However, similar to the superficial malar fat, it is subject to partial atrophy during the ageing process.

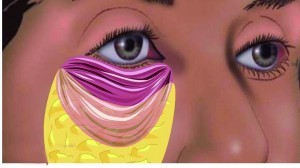

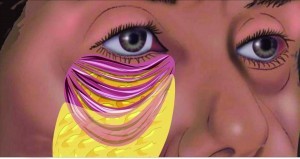

The orbicularis oculi muscle is a sphincter muscle responsible for voluntary movements; the constriction of the eyelids and elevation of the cheek, and of the superficial malar fat, which overlies it. The muscle contracts with laughter, elevating the lower eyelid and cheek. With age, it becomes less homogenous and less compact, losing its tonicity and spreading downward (Figures 4 and 5). Its fibres can become dissociated, resulting in gaps between them1, 4, 5.

The superficial orbital malar fat lies under the skin and covering the orbicularis muscle; the superficial orbital and malar fat gives both protection and shape by means of forming a fatty pad. A structure less dense than the deep malar fat, the superficial malar fat adheres to the skin.

The face is not static, but is dynamic. The orbicularis muscle is the principal motor in the mid-face for its movement in facial expression, and the superficial orbital malar fat is also involved in the mobility of this zone.

The face is not static, but ages. The resulting sagging together with the skin defines the palpebromalar groove, which with the mid-cheek groove and nasolabial fold forms the three principal grooves, and mark the changes of the ageing face. In addition, the orbital rim becomes more exposed owing to the fat loss and the descent of the superficial malar fat.

The internal part of the palpebromalar groove and the superior–internal part of the mid-cheek groove join together as a Y-shape to create the tear trough. Poets often refer to the hollow formed between the tear trough and the mid-cheek groove as the ‘valley of tears’.

The skin covers all these elements. There is a transition between the very fine palpebral skin and the thicker jugal skin.

To summarise, there is the deep fixed and static fat, and a superficial mobile fat, the latter being dynamic in the creation of expression and age-induced sagging. The skin, superficial malar fat, and orbicularis muscle are all mobile and dynamic. All move as though through a sliding space situated between the deep malar fat and the orbicularis muscle, and between the orbicularis muscle and the superficial malar fat.