Dr Jennifer David discusses the use of cysteamine 5% as a novel first line non‑hydroquinone treatment option bridging that gap between safety and efficacy in treating hyperpigmentation

Disorders of hyperpigmentation, most notably melasma and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, afflict a great deal of psychological stress on patients and remain a top concern at dermatology office visits1. These disorders also have a disproportionately higher rate of occurrence in the skin of colour population, which include those of African, Asian/Pacific Islander, Caribbean, Indian, Middle Eastern, and/or Latino descent. While the current cosmetic market is flooded with treatment options, most available products either lack efficacy or have a safety profile with a less than favourable risk/benefit ratio. Adverse events and drawbacks such as exogenous ochronosis, skin atrophy, photosensitivity, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and worsened hyperpigmentation have created a very large unmet need for a product that is both safe and effective1–4.

Hydroquinone has remained the gold standard amongst topical bleaching creams in the United States despite controversies regarding its safety profile. While the increased risk of renal carcinoma noted in rodent models taking oral hydroquinone was never directly correlated to topical human consumption, this along with the risk of exogenous ochronosis was enough to generate a warning report from the World Health Organisation (WHO) in 1997 and to implement a ban and strict regulation for the use of hydroquinone in Europe, Japan and a number of other countries in the early 2000s5,6.

Innovative approaches for treating hyperpigmentation started centuries ago, and a variety of agents were utilized to lighten disfiguring hyperpigmentation, including applications of borax, sulfur, tincture of iodine, potassium and sodium hydroxide, and ammoniated mercury. Prepared in complex formulations, they proved to be highly poisonous, and many produced rapid desquamation of the epidermis7,8. Intensive research on depigmenting agents in the 1960s led to the discovery and first clinical evidence of a molecule that was safe in mammals yet effective in inhibiting melanogenesis.

The discovery of the physiologic activity of cysteamine in skin pigmentation

Professor Chavin was a researcher of the American Museum of Natural History studying fish physiology. In the 1960’s he became curious about the metabolic functions of cysteamine, a natural antioxidant, in fishes. For one of his experiments, investigating the physiology of fish colouration, he injected cysteamine into the skin of a black goldfish. The goldfish scales changed from black-gold to a light-silver colour. Professor Chavin and his research team had discovered the physiologic activity of cysteamine in the regulation of skin pigmentation9,10.

Cysteamine: a physiologic pigment regulator

Cysteamine is the simplest aminothiol physiologically produced in mammalian cells. As a product of natural degradation of the essential amino-acid L-cysteine, cysteamine is biosynthesized during the co-enzyme A metabolism cycle14. The physiological level of cysteamine is well distributed in mammalian tissues, and its natural concentration is highest in mammalian milk. In milk, as well as in other tissues, this molecule acts as an intrinsic antioxidant and is known for its protective role15,16. Cysteamine is an agent with a proven safety profile, and it is antitumor, anti-carcinogenic, and anti-mutagenic effects are well recognised17.

In the skin, the intrinsic antioxidant activity of cysteamine acts by lightening melanin in the corneal layer. Melanin in the corneal layer of the epidermis can exist in an oxidized dark form or in a reduced lighter form. Reductant molecules can thus reduce melanin in the corneal layer to their reduced lighter form. This is, for instance, the mechanism of skin lightening action of ascorbic acid, which is used in high concentrations in cosmetic skin lightening products. Cysteamine is shown to be an effective reductant molecule and thus lightens melanin by reducing them to their lighter form in the superficial layer of the epidermis18, 19.

Despite its strong depigmenting effect, all efforts for making cysteamine into a topical cream for human use were fruitless due to the rapid oxidation of its thiol moiety. This oxidation would release a very offensive odour that could not be covered by perfumes, prohibiting its use in topical preparations26. Cysteamine was never developed into a depigmenting product.

A providential laboratory accident

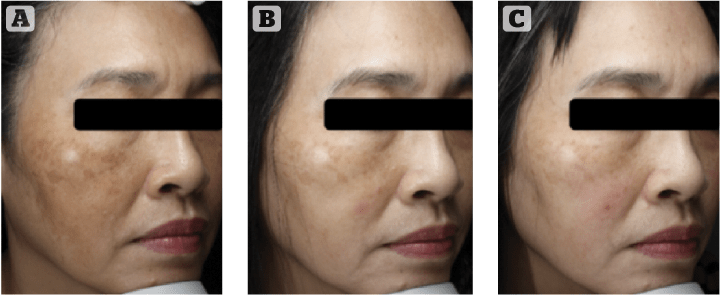

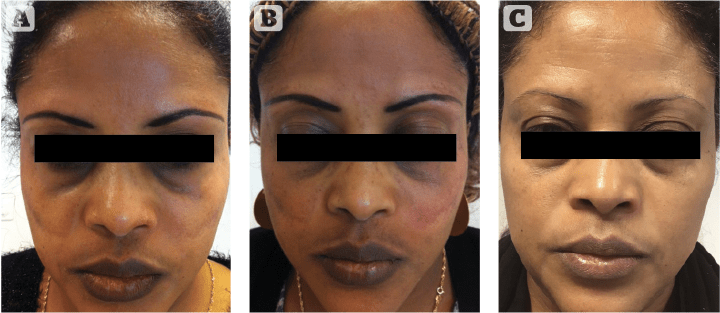

Figure 5 A melasma patient with an intensive treatment of cysteamine 5% Cyspera (15 minutes short-contact application once per day), pictured (a) before, (b) after 8 weeks and (c) after 12 weeks. Images courtesy of Dr Huang

After the WHO raised concerns about hydroquinone and a number of countries started to ban its use, pigmentation researchers resumed their investigations for safe and effective alternatives.

Dr Behrooz Kasraee, pigment cell researcher and dermatologist specialising in skin pigmentation concerns practicing in Geneva Switzerland, was searching for new depigmenting agents. He was always using cysteamine as the positive control, despite the skunky odour released by the molecule during his experiments.

One day of 2010, a providential laboratory accident during an assay preparation with cysteamine lead to a dramatic improvement in its odour and stability. Cysteamine was deodorized and now usable in topical preparations.

A novel first-line non-HQ treatment option for hyperpigmentation

Topical cysteamine 5% was born, yet its pigment correcting efficacy in humans was to be verified.

First clues were provided in 2013 at the AAD Annual Meeting in the form of a case series in melasma patients. Thirty female patients with epidermal melasma were treated once daily for 6 weeks with topical cysteamine 5% (Cyspera, Scientis Pharma). Dermatoscopic imaging, chromametric evaluations and histologic assessments were performed at the beginning and at the end of the trial. The investigator concluded that cysteamine was made usable for the first time in the treatment of stubborn hyperpigmentation, with considerable effects27.

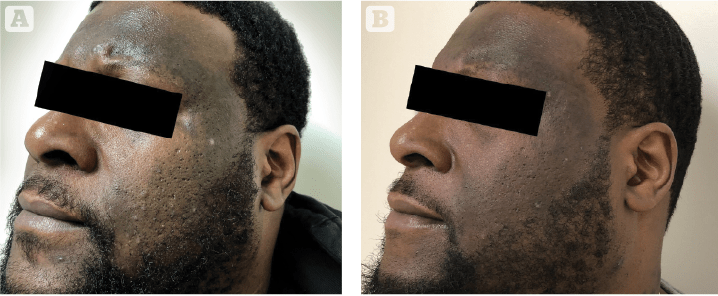

Figure 6 Male patient with untreated lichen planus pigmentosus, treated with an intensive treatment of cysteamine 5% Cyspera (15 minutes short-contact application once per day), pictured (A) at baseline and (B) after 8 weeks

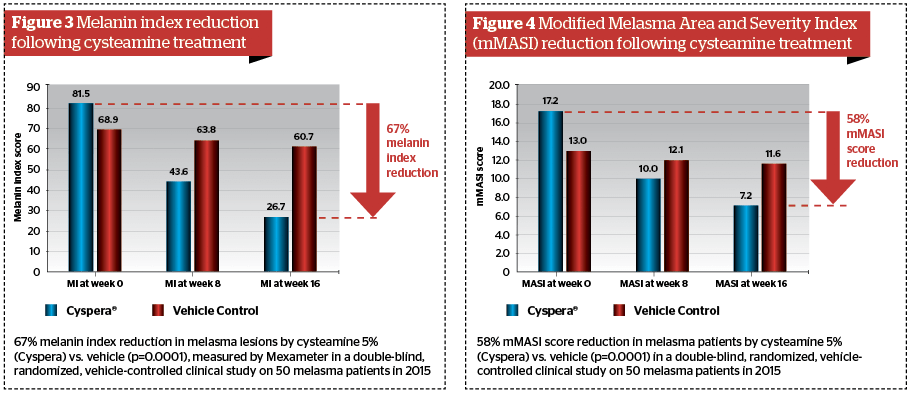

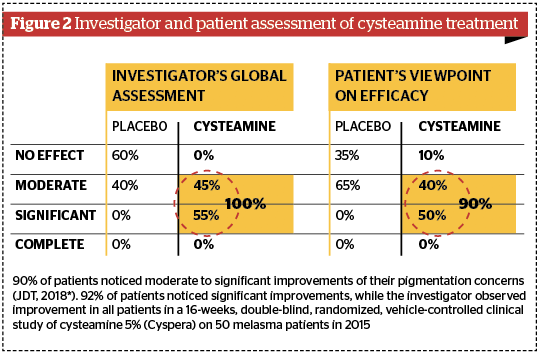

Subsequent high standard clinical trials have confirmed the significant pigment correction of topical cysteamine 5% in humans. The first landmark results came from a double-blind, randomised, vehicle-controlled clinical study conducted on 50 patients by Dr Mansouri in 201528. In 2017, this study was awarded the Heinz Maurer Award for dermatological research in ethnic populations. After 16 weeks, the mexameter evaluation showed 67% melanin index reduction in melasma lesions, with very significant P values (P=0.0001); the modified Melasma Area Severity Index (mMASI) assessment showed a 58% reduction in melasma patients (P=0.002); the global investigator assessment showed 100% moderate to significant improvement; and 92% of patients noticed significant improvements to their pigmented lesions. Other clinical trials have confirmed the efficacy results and indicated that undesirable effects are non-significant when the instruction of use is respected29. All investigators have concluded in the significant efficacy of topical cysteamine 5% in decreasing melanin content of stubborn pigmentation marks (Figure 2–4).

Are the emerging results of the comparison of cysteamine 5% versus Kligman’s formula a turning point? Kligman’s formula remains to date the dermatologists’ treatment of choice for melasma, yet side-effects and drawbacks are significant: ochronosis, skin atrophy, irritation, photosensitivity, and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Figure 7 Kligman resistant patient having full therapeutic response to cysteamine 5% (Cyspera). (A) Patient with phototype V had used modified Kligman’s formula (Pigmanorm) for 4 consecutive years with partial response and signs of skin atrophy due to this treatment. (B) Patient discontinued Pigmanorm and started an intensive treatment with Cyspera for 4 months (15 minutes short-contact application once per day). (C) Patient has maintained treatment with Cyspera for the next 5 years (15 minutes short-contact application once per day, twice-weekly).

In a new clinical study by Dr Karrabi (not yet published), the efficacy of modified Kligman’s formula was compared with cysteamine 5% (Cyspera) in a group of 50 patients with epidermal melasma using mMASI score, investigator global assessment, and patients questionnaire. Four months of treatment with cysteamine 5% or the modified Kligman’s formula showed that the mMASI scores were significantly reduced in both groups. Cysteamine 5% was more effective in reducing the mMASI score at both evaluation points of 8 and 16 weeks, although the difference was not statistically significant. Cysteamine 5% was significantly better tolerated than the modified Kligman’s formula by patients30. Sporadic cases are now being reported indicating that melasma patients who are resistant to Kligman’s formula can show a significant therapeutic response to cysteamine31 (Figure 5–7: before and after melasma).

These results indicate that topical cysteamine 5% is at least as effective as the modified Kligman’s formula. Non-melanocytotoxic and non-photosensitising, cysteamine also induces fewer undesirable and adverse effects, and even produces anti-mutagenic, anti-carcinogenic, and anti-melanoma activities. The high efficacy of cysteamine, as well as its high safety profile in contrast to Kligman’s formula, makes it a very promising alternative for the treatment of hyperpigmentation.

Conclusion

The unmet needs for a safe and effective depigmentation agent are very significant worldwide, particularly in our skin of colour patients. Concerns are most common in these populations, yet safe and effective treatment modalities are acutely lacking to them.

Cysteamine’s natural presence in human tissues and a long history of human use make it a safe product for cosmetic and aesthetic use. Now cysteamine is proving, through numerous studies, its high efficacy in skin pigment correction, and is a serious contender as a novel first-line non-hydroquinone option for the treatment of hyperpigmentation disorders.

Declaration of interest None

Figure 1 Adapted from Mansouri P et al, 2015, BJD 173 (1): 209–217, redrawn by Kevin February; Figure 2–4 Adapted from Mansouri P et al, 2015, BJD 173 (1): 209–217; Figure 5

© Dr. Huang 20 Skin, Taiwan; Figure 6 © Dr. Jennifer David, Schweiger Dermatology Group, Philadelphia PA, USA;

Figure 7: Adapted from Kasraee B et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019 Feb;18(1):293-295

References

- Pawaskar MD, Parikh P, Markowski T, McMichael AJ, Feldman SR, Balkrishnan R. Melasma and its impact on health-related quality of life in Hispanic women. The Journal Of Dermatological Treatment. 2007;18(1):5-9

- Handog EB, Enriquez-Macarayo MJ. Melasma and Vitiligo in Brown Skin. Springer; 2017.

- Handel AC, Miot LDB, Miot HA. Melasma: a clinical and epidemiological review. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89(5):771-782. Doi:10.1590/abd1806- 4841.20143063

- Pandya AG, Guevara IL. Disorders of Hyperpigmentation. Dermatologic Clinics. 2000;18(1):91-98. Doi:10.1016/S0733-8635(05)70150-9

- Parvez, S., Kang, M., Chung, H.S., Shin MK, Bae H. Survey and mechanism of skin depigmenting and lightening agents. Phytother Res. 2006Nov;20(11):921- 34

- Lau SS,Monks TJ,Everitt JI,Kleymenova E,Walker CL. Carcinogenicity of a nephrotoxic metabolite of the ‘nongenotoxic’ carcinogen hydroquinone. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001 Jan;14(1):25-33

- Klaus SN (2006) A History of the Science of Skin Pigmentation. The Pigmentary System, Oxford, Blackwell Publishing, USA

- Jacobi P (1904) Portfolio of Dermochromes. (2ndedn), Rebman Company, New York, USA

- Chavin, W.; Schlesinger, W. (1966). “Some potent melanindepigmentary agents in the black goldfish”. Die Naturwissenschaften.53(16): 413–414.

- ChenYM,ChavinW.(1966)TyrosinaseActivityin Goldfish Skin, Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 121(2):497-501

- Frenk E,Pathak MA,SzabóG,FitzpatrickTB. Selective action of mercaptoethylamines on melanocytes in mammalian skin: experimental depigmentation. Arch Dermatol 97 (4), 465-477. 4 1968

- BleehenSS,PathakMA,HoriY,FitzpatrickTB. Depigmentation of skin with 4-isopropylcatechol, mercaptoamines, and other compounds. J Invest Dermatol 50 (2), 103-117. 2 1968

- Qiu L, Zhang M, Sturm R, Aeta l. Inhibitionof melanin synthesis by cystamine in human melanoma cells. J Invest Dermatol 2000; 114:21–7

- Besouw, Martine; Masereeuw, Rosalinde; van den Heuvel, Lambert; Levtchenko, Elena (August 2013). “Cysteamine: an old drug with new potential”. Drug Discovery Today. 18 (15-16): 785–792

- Tatsuta M,IishiH,BabaM,TaniguchiH.Tissue norepinephrine depletion as a mechanism for cysteamine inhibition of colon carci- nogenesis induced by azoxymethane in Wistar rats. Int J Cancer 1989; 44:1008–11

- Hsu C,Pouramadi M,Ahmadi S,AliMahdi H. Cysteamine cream as a new skin depigmenting agent. Presented at the European Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting, Prague, Czech Republic, 27–30 September 2012

- Fujisawa T et al. Cysteamine suppresses invasion, metastasis and prolongs survival by inhibiting matrix metalloproteinases in a mouse model of human pancreatin cancer. PloS One. 2012; 7(4):e34437

- Hsu C, Ahmadi S, Pouramadi M, Ali Mahdi H. Cysteamine cream as a new skin depigmenting product. Presented at the 17th Meeting of the European Society for Pigment Cell Research, Geneva, Switzerland, 11–13 September 2012

- Kasraee B. “Deodorized cysteamine* as a depigmenting agent for the treatment of melasma.” Pigment Cell Melanoma Research. 2017;30:e27–e137

- Qiu L, Zhang M, Sturm RA et al. Inhibition of melanin synthesis by cystamine in human melanoma cells. J Invest Dermatol 2000; 114:21–7

- Kasraee B. Peroxidase-mediated mechanisms are involved in the melanocytotoxic and melanogenesis- inhibiting effects of chemical agents. Dermatology 2002; 205:329–39

- Benathan M, Labidi F. Cysteine-dependent 5-S-cysteinyldopa formation and its regulation by glutathione in normal epidermal melanocytes. Arch Dermatol Res 1996; 288:697–702

- Shibata T, Prota G, Mishima Y. Non-melanosomal regulatory fac- tors in melanogenesis. J Invest Dermatol 1993; 100:274S–80S

- deMatosDG,FurnusCC.Theimportanceof having high glutathione (GSH) level after bovine in vitro maturation on embryo development: effect of beta-mercaptoethanol, cysteine and cystine. Theriogenology 2000; 53:761–71

- SmitNP,vanderMeulenH,KoertenHKetal. Melanogenesis in cultured melanocytes can be substantially influenced by L-tyrosine and L-cysteine. J Invest Dermatol 1997; 109:796–800

- Hsu C, Ahmadi S, Pouramadi M, Ali Mahdi H. Cysteamine cream as a new skin depigmenting product. Presented at the 17th Meeting of the European Society for Pigment Cell Research, Geneva, Switzerland, 11–13 September 2012

- Hsu C. et al. “Cysteamine cream as a new skin depigmenting product.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2013) 68:4-1 AB189

- Mansouri, P.; Farshi, S.; Hashemi, Z.; Kasraee, B. (2015).”Evaluation of the efficacy of cysteamine 5% cream in the treatment of epidermal melasma: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial”. The British Journal of Dermatology. 173 (1): 209–217

- Farshi, Susan; Mansouri, Parvin; Kasraee, Behrooz (2017-07-26).”Efficacy of cysteamine cream in the treatment of epidermal melasma, evaluating by Dermacatch as a new measurement method: a randomized double blind placebo controlled study”. The Journal of Dermatological Treatment: 1–8

- Personal communication from Dr. Karrabi, 2019

- Kasraee B, Mansouri P, Farshi S. Significant therapeutic response to cysteamine cream in a melasma patient resistant to Kligman’s formula. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019 Feb;18(1):293-295